Slipstream Writers, Diversity in Speculative Literature, and Canonization

By Red_Harvey

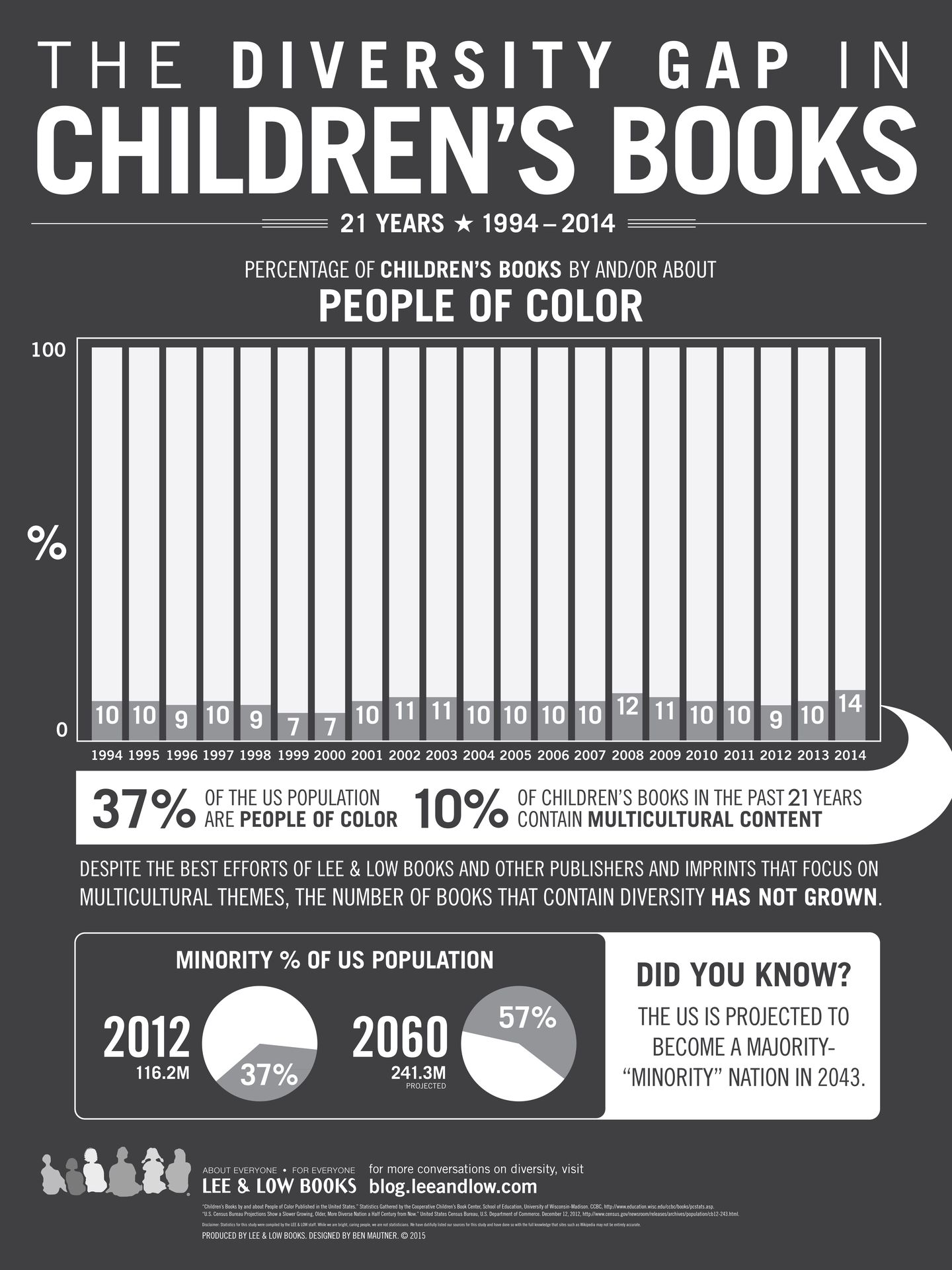

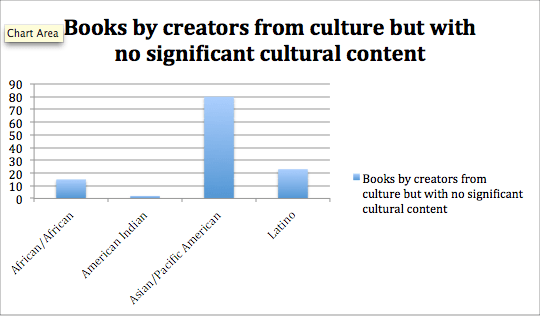

(while the pic below depicts stats on children's lit, the facts presented concerning diversity in literature are still startling)

Speculative fiction is a slippery minx, with many different definitions. My Otherness has given me insight into the purity of the genre. Not only am I an Other, but I'm a confused Other, who doesn't fit into just one Other notch. I've grown up surrounded by Hispanic culture at home, while being pressured to assimilate into white culture everywhere else. I've seen the value of Hispanic culture measured against white culture, and I'm struck by the parallels of how speculative stories are measured against "literary" stories. Seemingly, the classification of the sub-genres is related to the classifications of humanity into different gender, racial, and class pools. As an other-Other, I've wrestled with how impurity factors into my humanity, and have likewise considered how purity influences what is speculative fiction.

Certain undeniable elements comprise the whole of speculative fiction,such as John Clute's thoughts on "a [...] unique interest in the fantastic" (qtd. in Walter par. 3), or Darko Suvin's theory of melding familiarization and estrangement(qtd in Csernay-Ronay 119). While attempting to define this type of fiction,many do so from the historically dominant perspective of the white male. Though numerous, the white male is hardly representative of an entire culture, and yet, it's perfectly acceptable to reflect universal experience through white male eyes, or just white eyes.

When seen from another side, suddenly, the question of validity and fairness arise. For instance, 2015's Miss Japan is a hafu, or half-black and half-Japanese, and many believe that she is unable to represent all of Japan (Saberi par. 7).

In all fairness, she does represent a small minority in a largely homogeneous country, but her experience is continually negated on the foundation of her impurity. In a melting pot like the United States, with a higher percentage of minorities, a bi-racial leader (or writer or main character) might be better equipped to represent not only the dominant interests, but those of Others (and other-Others) as well. Through an overview of literature, I will analyze the prevalence of slipstream writers, the lack of diversity in speculative literature, and how both influence canonization.

Slipstream Writers

A slipstream writer can weave in between genres, and their body of writing defies definition. While some writers are primarily associated with fantasy,sci-fi, or horror, a slipstream writer dances across those lines so that a reader might say, "Yeah, she's a fantasy writer, but she's also written a sci-fi series. Come to think of it, she's also written horror stories...". Seminal examples include Ray Bradbury, Stephen King, Kurt Vonnegut, Ursula K. Le Guin,and Margaret Atwood. For instance, King is a strong horror writer, but he's also penned lofty sci-fi and fantasy epics, such as 11/23/63 and The Dark Tower series.

Bradbury, well-known for Fahrenheit 451, insists that even if he was labeled a sci-fi writer, he never felt like one: "many who observed that I was no writer of science fictions, [believed] I was a 'people' writer, and to hell with that!" (18). Before and during Bradbury's career, slipstream writing existed, but the name and ideology had yet to materialize. His lamentations of "people-writing" sound similar to Le Guin's constant reminder that her brand of sci-fi isn't really sci-fi, because her stories often revolve around social issues.

Concerning slipstream writers, the most interesting literary war to date has been between Le Guin and Atwood. In 2011, Le Guin published a review of Atwood's Oryx and Crake series. According to Atwood,she is unsure of the categorization of her work because she no longer recognizes what sci-fi is, only knowing it by "feeling" and not by "strict definition":

Though sometimes I am not asked, but told: I am a silly nit or a snob or a genre traitor for dodging the term...I didn't really grasp what the term science fiction meant anymore. Is this term a corral with real fences that separate what is clearly 'science fiction' from what is not, or is it merely a shelving aid, there to help workers in bookstores place the book in a semi- accurate or at least lucrative way?...These seemed to me to be open questions. (qtd in Thomas 3-4)

Atwood has always resisted the label "sci-fi", and until recently, I thought it was because she revered the speculative genre altogether. However, after reading some of her opinions in conjunction with Le Guin's review, I've concluded that she evades the term because she wishes "to protect her novels from being relegated [...] into the literary ghetto" (Le Guin qtd. in Thomas 7). Yet, writing off Atwood isn't as simple as all that. She struggles to define sci-fi, while also conceding to the complexities of the genre, which underscores the meaning of a slipstream writer. Le Guin's criticism, while a bit harsh, may have forced Atwood to examine sci-fi in the larger scheme of genre fiction, instead of viewing it from a rung in the classification of speculative literature, and a low rung at that. Or perhaps, Atwood re-considered her definition of speculative literature, as speculative and sci-fi mean very much of the same thing, because both hold the what-if element that Atwood herself has mentioned (qtd. in Thomas 60). An intentional disregard for genre is different from resisting categorization in the pursuit of staying true to story. While Atwood stays true to story, she misinterprets the value of slipstream writing, and undervalues genre writing.

Diversity in Speculative Literature

Diversity and slipstream writers are interconnected, because both are hard to understand, and both are continually denied throughout speculative literature. As tough as it is to receive recognition for slipstreaming, it'seven tougher to recognize diversity. A non-white male protagonist is a rarity.A non-white female protagonist is also a rarity. A non-white disabled female or male protagonist is the rarest bird of all. Pair that with a protagonist with anon-powerful position, and the odds further decline.

But so what? As long as the reader connects with the story, the protagonist's background is irrelevant, and whoever wrote the character did so without underlying bias.Yet, Aaron Passell speculates on the nature of the writer based on what they've written. If they mention violence, casual sex, beauty, or plenty, then such "details of these worlds tell us quite a lot, in some general ways, about when they were imagined and by whom" (Passell 60). Thus, by incorporating a majority of white male protagonists, writers are establishing their idea of the "right kind" of hero. Hiding behind the excuse of "story matters most", or "it's not my job to populate stories with diversity" is a clever way to avoid issues, because one of the apparent issues is the lack of diverse characters in stories.

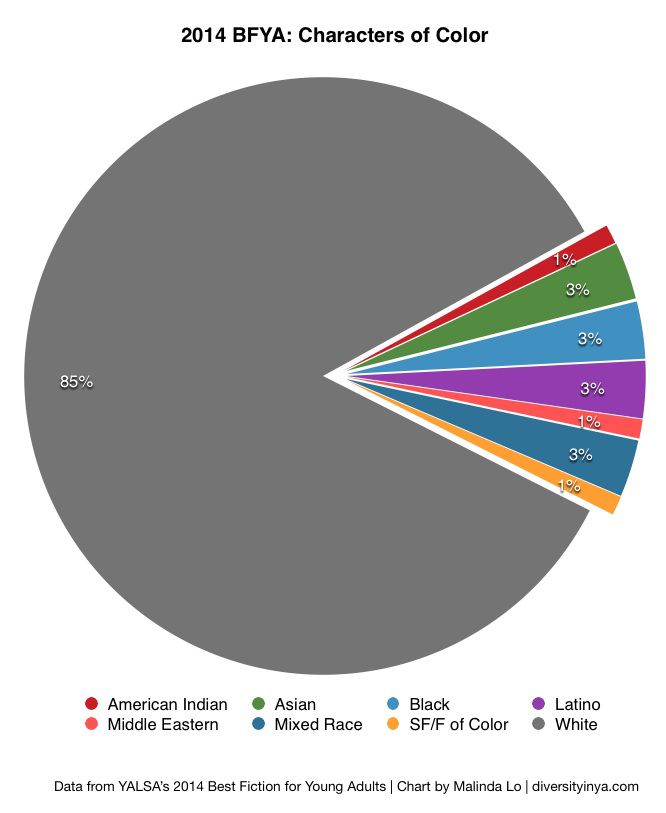

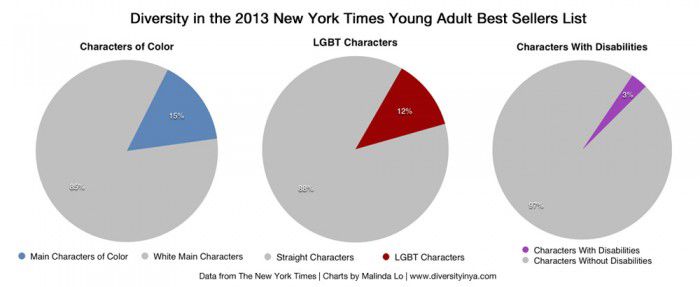

Nevertheless, writer Elif Shafek is wary of identity politics in literature. As a minority, she's been criticized for not including enough minorities in her stories, which she finds distasteful (TedTalk). She believes the story is what matters, and will serve as enough of a transformative experience for the reader. To a large extent, story is the guiding principle and no writer should be forced to inject stories with identity issues. At the same time, "novelists are embedded in the social dynamics of their time", (qtd. in Thomas 60). Crafting a story around issues can be measured on a spectrum, with authors like Samuel Delaney and on one end, and authors like Meg Rosoff on the other. Recently, Rosoff found herself on the end of a social media storm after commenting about the "job" of a story. In her words, many books speak to marginalized children, and "good literature does not have the 'job of being a mirror'" (Rosoff qtd. in Flood par. 1). Before offering an opinion, Rosoff would've done well to check her facts. In Young Adult fiction, Wetta reports that minorities"make up about 37% of the population in the United States, less than 10% of books feature diverse characters", with the overall percentage in sci-fi ranking even lower (par. 1). It's unfair of Rosoff, or others like her, to discount the value of representation in literature. As a white woman, she has several mirrors from which to peer through, while the black gay character she publiclydisparaged has virtually no standing in the literary world.

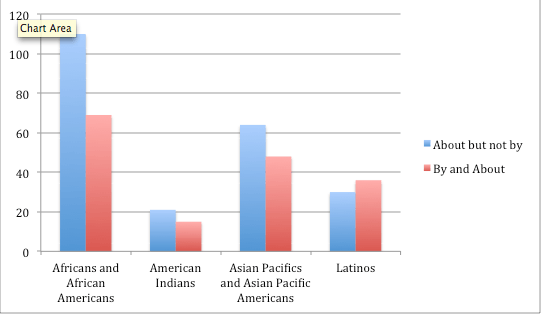

Original data taken from the Cooperative Children's Book Center: http://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/books/2014statistics.asp

Original data taken from the Cooperative Children's Book Center: http://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/books/2014statistics.asp

World building, orthe process of creating an unfamiliar world full of familiar characters, is an important tool for writers. Even as some argue that the role of speculative fiction is escapism, others believe the nature of world building provides a platform to analyze real-world issues. N. K. Jemisin, a writer criticized for being outspoken, says that it's a writer's job to know and care about world issues, because "for the world builder, all the world is necessary fuel" (qtd. Hayman par. 10). Popular fiction, like Harry Potter, Hunger Games, and Game of Thrones, are socially relevant and entertaining, but their artistic worth and storylines might deepen if they were to include characters and storylines of a diverse nature. Put another way: "stories that ignore or overlook the realities of oppressed and marginalized groups (or seek to replace them with fictional analogues like elves, ogres, or vampires)can also undermine their own potency and potential" (Hayman par. 3). A story's worth is eternal, and inclusion of characters should reflect that fact. Eventually, the most valued stories are canonized, and as this presentation has shown, representation is lacking in both characterization and definition. A canon is built on the ideas of what is, and speculative literature is essentially ephemeral.

Effects on Canonization

When slipstream writers and diversity are undermined, the effects cross-over into shaping the canon. So much of slipstream writing is about opposing the status quo, and that is what spreading diversity is all about. Thus, the denial of one or the other (meaning a denial of diversity of a denial of slipstream writing) is really a veiled denial for change.

Like so many, Jennifer Lyn Dorsey views sci-fi as the genre of change. While presenting new ideas, the stories "thrusts readers out of their comfort zones" (Dorsey qtd. in Thomas 75). The same theory can be applied to horror and fantasy, which displace the reader, and force them to view character interactions in new ways. All three types of speculative literature are engineered to explore new themes and perceptions. Not every slipstream writer is diverse, but chances are, any slipstream writer will explore themes related to social realities. These days, the awards in the speculative realm feature a smorgasbord of diversity, at least on the sci-fi side. Horror stories are catching up, with fantasy lagging behind, but not by much. Ultimately, the nominees and award winners will add to the canon.

Since awards and critics bring acclaim, their opinions matter. Stories featuring social issues are debated for their sci-fi cred, with some wishing to toss them into the realm of fantasy literature, or if a story is crowded with too many conflicting literary elements, some believe it shouldn't be considered at all. By denying slipstream writers, or denying a genre, the story is mis-categorized or overlooked completely. As Le Guin notes, messaging isn't where a story should start, but that doesn't mean a reader won't perceive a message through the story (40). Other literary critics like Jonathon Sturgeon view an adherence to genre as "tyranny", even as he acknowledges countering narratives:

"Kazuo Ishiguro a fantasy novel. He doesn't want to call it fantasy. You know what?That's absolutely fine. He can call it what he likes. Ultimately, it's his readers who will decide what it is, whether they want to slap a label on it anyway. If you consider yourself a fantasy reader, then read it. Or don't. Have your views on it – you're entitled to them".

Admitting a story belongs in a particular genre doesn't diminish it. Denying genre placement altogether disparages the genres. There's nothing wrong in placing a story full of dragons and ogres in the fantasy category. A fantasy story is not mindless or formulaic, despite Sturgeon's claims (par 4). The best part about a fantasy(or any genre) story is that it's not just a fantasy story. Like Bradbury, LeGuin, or Carroll's work, fantasy borrows from other genres. I believe the fear in acknowledging genres is the belief that genre work isn't literary and vice-versa. Case in point, Sturgeon asks: "Is Kazuo Ishiguro's new novel, The Buried Giant, a work of genre literature? Is Beowulf?" (par. 1).What he means is, are the two stories legitimate literary works worthy of canonization? Of course they are, and so are many other speculative stories that are overlooked because of surface-y tropes. Notable fantasy series are studied for far more than their use of dragons or magic, like The Lord of the Rings, Earthsea,or Parable.

Each series is centered on story, but reader interpretation carries messaging through. Furthermore, a misunderstanding of slipstream writers coupled with a denial of diversity is an affront to the identity flux already underway. According to Morris, the US is "in a midst of great cultural identity migration. Gender roles are merging. Races are being shed. In the last six years or so, but especially in 2015, we've been made to see how trans and bi and poly-ambi-omni- we are" (par. 4). Genre writing is a commendable practice, and although no writer should be tied by their use of time travel, dragons, or zombies, they shouldn't downgrade the genre tropes either. By pulling from a casual categorization, writers like Ishiguro also shape the canon by leaving only entertaining stories to choose from, while they populate the "literary" lists with their work.

Conclusion

As a slipstream writer and an other Other, I understand the confusion that comes in finding a niche. I applaud anyone who challenges the status quo, and I continue to raise questions on the definition of speculative literature. Speculative stories are pure and entertaining. Yet, impure writers who bend the rules sometimes abandon ship, further confusing the masses as to the validity of genre writing.

Due to the prevalent themes of ostracization, speculative stories appeal to minorities. While everyone relates to feeling left out, the feelings are amplified for minorities. Factions of Others may read such stories with greater consumption. Therefore, increasing diversity of characters and experiences is a smart move, if merely to appeal to a growing readership.

As an Other who's never fit into one label, I realize my premise is contradictory: writers, come one and all, conform to the labels! Labels can create harmful stereotypes. As bell hooks reminds readers, she isn't a black writer, or a female writer, but just a writer. However, I'll continue to waive my Other card around to illustrate that I know the difference between denouncing all labels and absorbing them. I'm not just a woman, mother, Puerto Rican, or Bob Dylan enthusiast, but all of those things culminate in the vast space of me. I am not one designation, but many. So it is true for genre fiction, as well. The Lord of the Rings is fantastic, romantic, poetic, epic, and literary. Labels, useless as they are on their own, build up to a larger tapestry of meaning. Though rich and varied, a tapestry has to start from somewhere.

*****

A/N: This is a paper I presented at a conference, met with mixed reviews. I apologize for the length (which is what he said), but I hope you vote and comment. Call me on my bullshit, or praise my findings! I love debate either way :D

Oh, I was gonna post the reference page, but it's hella long. If interested, PM me.

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: Truyen247.Pro