Chapter Five

For the first time in months, Abraham felt bloated. He hadn't been able to finish his half-portion of rice, filled to contentment with barely half said share. He'd eaten three meals that day. Three small meals that brought color to his cheeks. He hiccuped and blushed. It felt so good to be spoiled after so long. He had no intention of telling them that he could offer no recompense.

"Again, Mr Walters, I apologize for not giving you better care in your state," William Octienne said.

"There are no relief teachers in West Haven, unfortunately," continued his wife, Jen. The couple were opposites. Him, dark-skinned and neatly dressed and she, fair-skinned and freckled with rag-like attire. "We must be with our students during the day, doing what we can."

Abraham peered between them through hooded eyes. They did most of the talking. He had spent the better half of his day alone, sleeping off an extraordinary hangover, and recovering from his restless months of travel. William had appeared briefly to fix him lunch, and then left him to himself. How they trusted him so easily in their home, he could not fathom. William had even allowed Abraham the use of his razor. Used to an electric razor, Abraham had riddled his face with shallow cuts. Small cloth swabs stuck to his face.

"I'll mix you some medicines tomorrow, if you can tell me what ails you," William offered. "Speed up your recovery."

"Oh, how kind." Abraham did wonder when they would realize that he could give nothing to them. He had learned from a very young age that to give was to take. Generosity was simply a form of trading; something was always expected in return. Pity for them. He would milk them of all they had until he could move on, back to the city. He had plans for when his strength returned.

"I have an oculist friend on my level at the college," Jen said. "I could ask her to make some new lenses for your glasses."

"Truly? You are a godsend, ma'am. I have the eyes of a mole."

They'd moved from the dining table to the fireplace purely for his comfort. He'd eaten his meal in an armchair before the flames, pampered like a house cat, nearly put to sleep by the soothing warmth. Jen sat in another armchair, while William had pulled a stool from a cupboard for himself. The couple finished off their servings and the husband took in the plates.

"I'll put this away for your lunch tomorrow," he beamed to his guest.

"Oh, thank you." Abraham blearily watched his rice go. He found it strange that there was no wall separating the lounge from the kitchen and dining area. It was all one dreadfully plain room.

Jen drew a well-used notebook from her pocket. The woman was covered from head to toe in black grease and oil and soot. Filth slicked strands of her curly orange hair and stained the purple bandanna that held her fiery mane out of her freckled, smudged face. Abraham had wondered about her state since she had walked in the door that evening, but hadn't asked. William barely seemed to notice, so Abraham assumed it was nothing out of the ordinary for the Octienne household.

Boiler trouble at their workplace, perhaps? Abraham thought.

She had been perfectly clean in the morning. "Besides undernourishment, is there anything bothering you? Any wounds? Anything hurt? Do you feel faint, at all? We'll make a list for Will."

Abraham didn't let his smile show. How could he resist such thoughtful care? He didn't hesitate to exaggerate.

***

Alyn crouched by the dying fire and watched the embers pulse against the dark. Earlier in the evening, the corpses had been reduced to pulpy red and black charred skeletons and ash. The buzz of flies had waned, many burned, many fled. Alyn could barely recognize the mess as bodies anymore.

Master Hughes cleared his throat behind her. When she gave no acknowledgement, he touched her shoulder. "Kid."

She looked up, disoriented. Putrid fumes filled her head, putrid sights filled her eyes.

"Come away."

She clutched his sleeve and started to stand. He helped her.

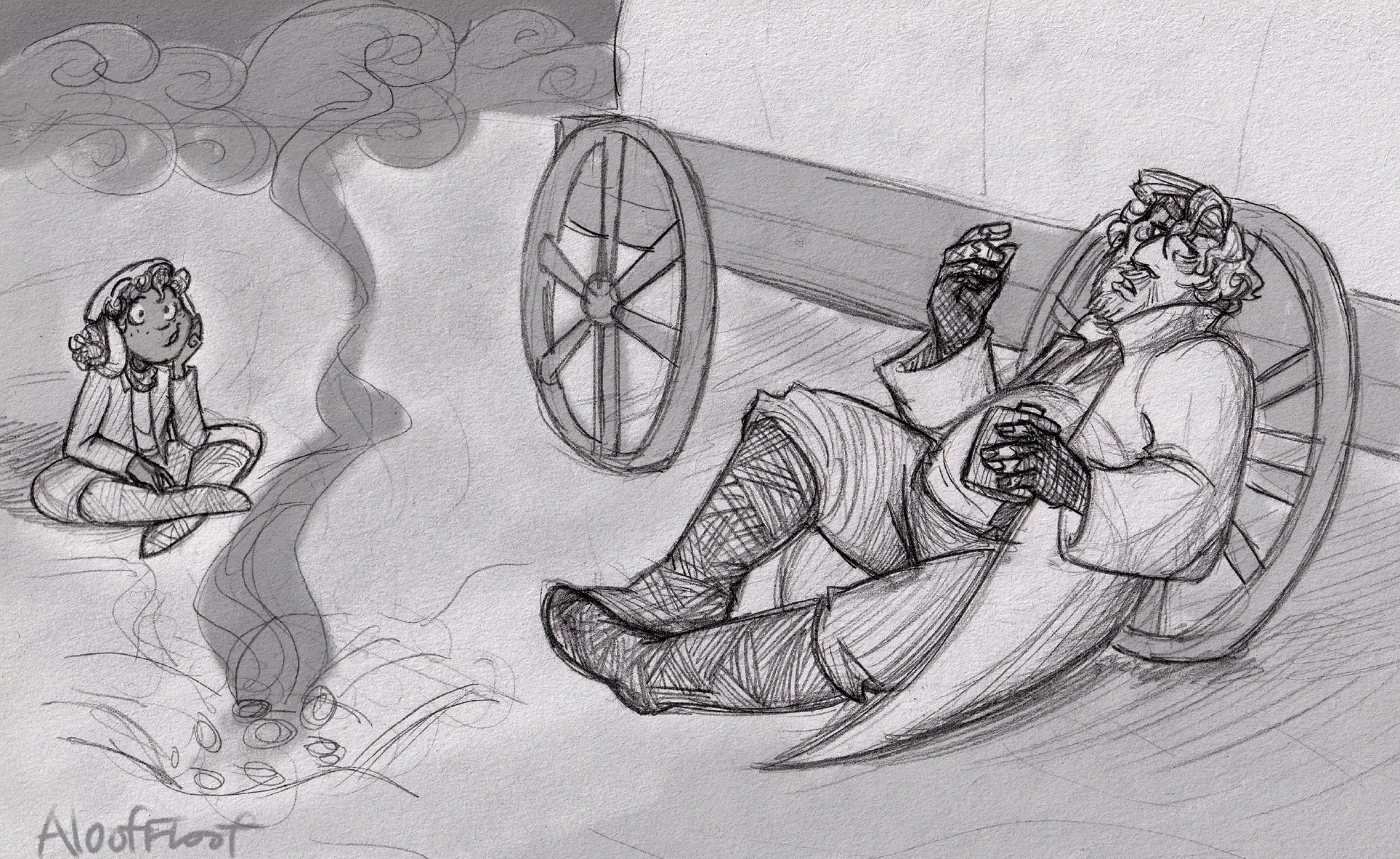

They walked silently around the dilapidated old steam engine, away from the corpses, to where Master Hughes had built a cooking fire. The scent of baking potatoes and beans sent the girl reeling. She crumpled to her hands and knees and gagged. Hughes wet his lips. He stood over her for a moment, then walked past and settled by the fire.

He served a small portion of food for her and set the dish on top of his hat, raised from the sand. Then, he filled his own bowl and started to eat.

After a while, she joined him, rubbing her teary eyes.

"You watched the whole time?" he asked, without looking up.

"Yes."

"You're stupid."

She reddened, nose burning. She took her dish onto her lap and started to pick at the food. As she ate, the queasiness in her stomach slowly lessened and lessened. It distracted her—good food, much better than that she received at Dumbberry's—from what she had seen. With each swallow of her meal, she swallowed the memory deeper and deeper down. It would do no good to dwell.

The blacksmith exchanged almost no words with the her. When she started to speak again, he answered only to silence her and cut off her questions. When she started to feel her energy coming back, he told her to sit still. He stood up and went to his toolbox in the wagon and returned with a crowbar. With it, he started to strip metal off the train, taking whole panels.

"What are those for?" she asked. He continued to pry in silence, building up a pile of the sheets. Eventually, he stopped to pick up the pile and carry it to the wagon. This time, he returned with a belt of knives and sat again in the light of the fire.

"What are you doing?" Alyn asked.

He unrolled the leather belt.

"Why'd you tear up the train?"

His whiskers twitched and he frowned and took out a knife and a grinding stone.

"What's all that metal for? What're you doing with those knives?"

"Shut up, stupid girl!" He kicked a smoking ember at her, and she stayed quiet for a while. Just over an hour later, his eyelids started to droop. It wasn't all at once, but, as time went on, they grew less and less willing to stay open. During the interim twixt sleep and supper, he sharpened the set of knives. Every so often he would sip from his flask.

Alyn observed him quietly. When the last knife lay, shining, in the pile with the rest, she spoke up. "Master Hughes?"

His tired eyes, ringed with shadows, narrowed. He began to neatly organize his knives on their thick leather belt. "Girl."

"Master Hughes," she continued, impassively, "What are we doing? What's in the city that's gonna stop sick refugees from getting' sick and wandering?"

Hughes paused, leaning over the leather knife-belt. "The Shirs," he said. "They own the cure for the plague, and the radiation that causes it."

"So, we gonna rough em' up a bit?" She put up her fists and bounced them through the air like a boxer.

"Rough them up..." Hughes repeated, brows pinching. "Something like that."

She slid her fingers into the dirt behind her, leaning back and propping herself up. "Tell me about them."

"They are bad people."

"So? Why?"

"Their ethics are... controversial."

"Ethics? Con-truh-ver-shul?"

He flinched. His eye twitched. His answer took its time to come, bitterly muttered. "A lot of people disagree with them."

Alyn hummed her understanding. A brief silence followed, where her fingers vibrated double-time against the dirt. She bit her lip and whined, then blurted out, throwing up her arms, "Oh, come on! I know that you know more! Master Octienne told me you did! Ah could tell for myself, anyways, just like you knew all that histery stuff you told me 'bout with that Depression thing and all the old junk around here. Ye're smart! Ah'll listen, you know. I'm your apprentice, and sorta like your partner, now. You should trust me! Tell me about things! I know ye're not a big talker, but, I mean, you haven't answered even one question about yourself, or your things, or—"

"You are not my partner. Apprentice, maybe, but not partner," Hughes corrected firmly. He rolled up the belt and set it on his lap. For a moment, he paused. One eyebrow thoughtfully perked. He scratched his whiskers. "All right," he said. "I'll tell you what you ought to know, for the sake that you ought to know it, on one condition."

"What's that?"

"Stop trying to talk to me," he glowered sternly. "Speak when spoken to. You may not be the sharpest tool in the shed, but even so, it's not such a difficult concept to understand."

Alyn frowned. "Well, when you don't answer my questions, it's like you got secrets to hide. But, fine. Speak when spoken to. Yeah, I get it."

Master Hughes leaned back against the train and set the knives at his side. He picked up his flask and rested it, in his hands, on his protruding belly. "I won't be repeating myself, so listen closely." He spoke to the dark and dusty sky rather than to his undesirable company. "The Shir dynasty truly began in the 25th century with Delmont Shir. As I already explained, this was the Second Depression. Nuclear warfare." He drank from his flask. "Like most intelligent people, Delmont spent much of his time in underground bunkers, covering every inch of his skin to avoid being killed by the fallout. In the later years of this century, the radiation reduced enough for him to safely go outside.

"Now, Delmont was a smoker. After cigarettes were legalized mid-25th century, he was right into them. He saw opportunity, knowing that there were many like him who craved them. This was how Ban-Ken began.

"It was a small settlement in Kentucky which Delmont helped to found. The area had been less affected by the war than most of the rest of the state. After clearing rubble and building shelters in the area, Delmont started up his own business. Tobacco. The wealth came quickly."

"I had a cigarette once," Alyn remarked. "Didn't taste very nice."

"Shut up and let me tell the story," Hughes barked. "You asked for it, you listen."

"Yeah, all right," Alyn muttered. "Simmer down."

"Generation after generation of Shir descendants cultivated the tobacco farm, and over time their business and land expanded. They became very wealthy and very powerful, and very, very greedy. By the late 27th century, every business in the growing settlement of Ban-Ken ran under their rule. It was a nice place, then. The kind of place that people scrimped and saved to make a life in.

"Then, Professor Ferdinand Polcene came with his great inventions—living, breathing creatures that he called fauns—and Elaine Shir got greedy. You see, these fauns were capable of great things. They were bred with complicated technology and biology that, through controlling cell division—"

"What?" Alyn interrupted.

"That, through controlling cell division," Hughes continued testily, giving her a pointed glare, "could be used to grow plants and restore the environment—just with a touch of their incredible fingertips."

Alyn's brows raised at seeing a flicker of excitement cross his face and raise his shoulders. She grinned.

"That was Professor Polcene's goal; to restore the Earth to green," Hughes continued. "Unfortunately, Lady Shir saw a different use for the technology. What was made to save our dying planet, to restore what mankind destroyed, she saw fit to use for self-preservation."

"What's that?"

"She wanted to use it to extend her life. To hell with the plants and the greenery and the Earth! Hogwash, all of it!"

The girl's grin broadened.

"The same cell division technology that could grow seeds and heal plants could be, Polcene confirmed, tweaked to provide eternal life for humans. Polcene did not agree with this use of his technology. It was ethically, morally wrong. He tried to keep his research from her, he tried to stop her from getting her hands on his work. I said it earlier; Professor Polcene burned in a fire on the sixteenth of August, in the year two-six-oh-three—this was the day following his presentation of the fauns. In that fire, he took with him his self and his knowledge, and all his years of notes and findings, just to keep them away from her—the Lady."

"Jiminy," Alyn breathed.

"In my own research," said Hughes, with a sniff, and sip of liquor, "I have never been satisfied with the amount of information I have managed to scrounge on what happened to the fauns that day. What is common knowledge is that twenty-eight fauns were captured and, to put it briefly, worked to their deaths in the Shir laboratories. Lady Shir was impatient and forced her scientists to work on Polcene's creatures, to try to understand and replicate them, until they couldn't take it any longer and they simply... died. Her scientists didn't have the secret to eternal life, but even today, they are working on replicating it for her. As a side, there were originally thirty-two fauns, proven by a photograph that was found in an Invincible™ wallet in Polcene's laboratory remains after the fire. No one knows what happened to the four unaccounted for fauns."

"Maybe they're still out there, wandering!" Alyn exclaimed.

Hughes scoffed. "I've wasted too much of my—" He stopped himself, pinching the bridge of bulbous nose. He shook his head. "Lady Shir's experiments into attaining eternal life have given her city a lot of grief, but the Shirs are careless. Because of those experiments, people are dying, many used as lab rats, stripped of rights. A great deal of the more dangerous failed, and even some of the successful attempts at recreating the nanotechnology and its biological effects over time built up toxic radiation, which is the cause of Ban-Ken's terrible plague. Radioactive decay, from the portion of the experiments that used radiation and nuclear power. The Shir family formulated an antidote and were immunized against it, but they left the rest of the city to endure without."

"Wait, so, Elaine Shir is still alive? I ain't much good with numbers, but—"

"She has lived for over two-hundred years. One would think her scientists did well, but... Not well enough," Hughes grimly replied. "They developed a technology based on the information collected from Polcene's inventions, but it isn't the same. It is powered differently. It doesn't give eternal life, it can't heal injuries in seconds, and it certainly can't grow seeds— as was Polcene's humble intention. Lady Elaine's nanotechnology siphons life from others. She absorbs the victim's biology, and absorbs their life."

"That's gross."

Hughes made a face and turned his flask upside-down. A single drop wet the sand. "I wouldn't think gross would be the right word," he grumbled, and slipped the flask into a pocket. He laced his fingers over his stomach.

"Why didn't they give the cure to their people?"

He scratched his jaw. "It's complicated. It used to be less so, I think, but according to that scoundrel, Walters, it's become some sort of tool for eugenics. The cure is only given to people that work for the Shirs or pay a great deal of money. Therefore, they are selecting the wealthy and those willing to agree with their ideas and methodologies to survive."

"You-what-ics?"

"Creating a master race. Selecting for a certain class of society to be denoted 'perfect'. You and I would probably be scrapped." He shrugged and rubbed his nose. "Anyways, Lady Shir gave much of the control of Ban-Ken over to her eldest son a few decades ago. Lord Pallis. He'd be close to seventy, now. Like Elaine, he is interested in eternal life, and is willing to let people die for the chance that he may live forever. Some people say he enjoys letting people die. Enjoys killing them himself, even."

"You said eldest son. So's there another one?"

"Berthold," Hughes nodded. "Berthold was different. They say he tried to talk some human decency into the family, talk them into helping their town. Obviously, they didn't listen, but, he gets credit for trying, I feel. At some point they say he took matters into his own hands and started to sneak the antidote to the townspeople himself. He was the closest thing Ban-Ken had to a hero. But, in the long-run, nothing changed. He was caught freeing the first wholly successful test subject since the beginning, and was promptly banished. Rumor is he very unheroically... well, he disappeared a few years later, presumed dead. I've not heard a breath about him in the years since, but I think some people still naively believe, or hope, at the very least, that he's still out there."

"What about you?"

"For his own sake, I hope he is dead. Doing jackshit and somehow managing to hide for thirty or forty-odd years only asks for resentment from me. It's cowardly."

"How do you know so much 'bout everything?"

Hughes sighed. "Because, unlike you..." He paused and concentrated on the small flames that danced over the remaining coals in the fire pit. "I can read." He pressed three fingers to his temple and made a face. "All right, we're finished. What happened to not asking questions?"

Alyn grinned. A laugh rose from somewhere in her throat. "Well, saying that only makes me want to ask more questions! Ah told you; it makes me think ye're hidin' something when you don't answer."

"Think what you like, stupid girl," the blacksmith muttered. He raised his hat to his head and angled it to shade his eyes. "We arranged that I would tell you of the Shir family, and you would speak when spoken to. I've done my part."

Alyn shrugged and slyly wiggled her brows. "And I've done mine. You spoke to me, so, the way I figure it is, I can speak."

Master Hughes snarled. "If you question me more tomorrow, so help me, I will cut out your tongue myself. You are an absolute nuisance. Now, get to sleep. It will be twelve hours or so on the road, starting at first light, and you will be driving."

"Twelve hours?"

"Sleep, girl. If you aren't up and ready to go when I am, then I will leave to Addinburgh without you."

Alyn scowled. They were silent for a few minutes, and she saw him gradually relax. She chewed her inner cheek. "Master Hughes?"

He did not answer. Moments later, he quietly began to snore.

Alyn lowered her herself to the dirt and curled up as small as she could before the last of the embers. She was glad he had spoken. Not about himself, perhaps, but it gave her some comfort to know that there was so much knowledge within him. He knew about things; things like where they were going, what they were doing. He knew about things like the world. And she thought, in the bleary interval before sleep, that maybe knowing it all was what him so sad. He carried with him the weight of the world—the burden of an experienced man.

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: Truyen247.Pro