The Corpsewood by @FinnyH

October 14th, 1887

My dear, do you remember the tale of the wolf and the lamb? It was the lamb who paid the price of being eaten at the wolf's first opportunity – a creature leaning on flimsy excuses for his own gain. I would like you to remember this fable when you read through these letters and realise I am not the wolf that people pretend I am. Nor may I claim the innocence of the lamb, dearest, but I am both, in a disturbing likeness to Henry Hallenbeck's perverse creation.

If this does not make much sense to you yet, it will. It begins with my trip to the uplands of Dartmoor, though I never did tell you my true intentions there upon departure. It was not to act as Emory's witness during the autopsy of our esteemed colleague Hallenbeck, which I declined out of lingering sentiment for the old fellow, but to follow the only lead I have to discover the queer circumstances of his death.

As you are already aware, Hallenbeck immigrated to Whitechapel shortly after we relocated there. I believe you met him once and commented in private on the lilts of his Dutch accent. As I recall, you said it gave him the kind of exotic homliness only those from the mainland could declare, but your words were perhaps the kindest he ever received while in Whitechapel, even if given inadvertently. I am certain back then neither of us knew his intentions would turn out to be evil, but we understood early on from his reputation that the man was somewhat misguided.

I did not immediately pass judgement on him when once I learnt his name, however. My sweetheart, I beg that you do the same for me and keep the knowledge close to your heart that what I did to those five women I did for us.

My journey to Dartmoor went without hindrance, though the ride was long and the rainstorms longer. I arrived at the Wych Elm Inn near Two Bridges yesterday morning and my driver kindly offered to help me upstairs with my suitcase. I believe he said his name was Edmund. Not a very talkative man by any stretch of the imagination, but I left him an extra shilling to buy himself a warm drink before his sodden journey home. With November on the approach I cannot say I envied him.

I was thankful for a more substantial bed after my days on the road at least, and I found my room at the Wych Elm accommodating if not a little modest. The windows in my room were a drafty and howled fearsomely on nights that the winds descended Beardown Tor from the north east. But for the price and sheer isolation of the place I could not complain. And isolated it was, for there was no road for almost a mile and the nearest dwelling was the south groves of Wistman's Wood itself.

The view from my room whisked me away to the lands of some fantastical fairy tale when once I caught sight of the enchanting little wood in its whole. I wish you could've seen it, dearest. I feel you'd have stared out upon the vast, untouched moors and the leaden backdrop of clouds and lost all sense of minutes and hours like I did. By the time I tore myself away and thought to unload my suitcase I considered it strange how the hands on my pocket watch showed it to be already past noon, despite Edmund having only closed the door behind him moments prior. I'm quite sure I had wound the watch only yesterday, but I have been known to misremember life's finer details. Perhaps the journey had taken its toll on me after all, or I really had been stood at the window for hours. I nevertheless wound the watch again, just in case. You never can be sure how the altitude affects these contraptions.

After a wasted day I bargained with myself that tomorrow would not be the same. I had hoped to weather up and trek the uplands towards the wood that first afternoon, but after sitting down on the bed to skim Hallenbeck's final letters one last time, I rather felt as if my energy had been sapped. It was odd. As if both myself and my pocket watch had suffered the same fate, somehow. Regardless, I feared the rainstorm would not permit my wanderings anyhow. Even now I'm yet to see any sign of ample break in the downpour. So much for the southernly weather. I thought if the lead I had on Hallenbeck's final hours does indeed point me to Wistman's Wood, I would rather not be caught up on the tors past nightfall.

I decided to eat what remained of my lunch and retire early for the night, as it seems the darkness descends swifter here in Devon than London. At what feels like only three in the afternoon, I can hardly keep from yawning.

Yours, with love.

October 15th 1887

It is not unusual for me to dream of Hallenbeck's chimera, and, dearest, that first night I visited it again quite clearly. I remembered the beast fondly the first few times, being that I was only an impressionable eight years of age when I encountered it. Not to mention that the creature had also been – to my father at least – something of a marvel. Come to think of him I don't recall much else of the man; perhaps only his modest choice of footwear and the way his smile never reached further than his moustache. But I do frequently dream of the inner city zoo that housed the beast, and how it came to be that Henry Hallenbeck had nicknamed me Jack.

Back then, not only was Hallenbeck an explorer, zoologist and, spoken behind hands, at the mercy of a gambling habit, he was also a self-styled Anomaly and Chimera Keeper. I asked him once when I was young why he'd thought to embroider ACK into his breast pocket and he explained to me what the acronym stood for. He'd laughed when I stumbled over repeating the words.

"And you, boy," he stooped down to say, "may one day be my Junior. J.A.C.K. How do you like the sound of that, Little Jack? Would you like to be an Anomaly and Chimera Keeper too?"

Needless to say I'd nodded vehemently, hardly realising the perversion it took for a once God-fearing man to distort the Lord's design and create his own mangled abominations. It is no accident Hallenbeck chose for his first monstrosity to combine the wolf with the lamb, as if to announce his own warped morals.

But I digress, my dear, because I did not dream of Hallenbeck's chimera to speak poorly of my departed friend. It is said to dream of a wolf symbolises survival and pride, but to dream of a lamb foretells my own vulnerability. So what would you say it means to dream of Hallenbeck's chimera? Of that limp and hairless canid sporting the head and forelimbs of a young sheep from its spine?

When first I woke on that second morning in Dartmoor, I thought not much else of it but a frightful testament to the man who created it. It is only after I followed the lead to Wistman's Wood that I reassessed its meaning.

The morning sky fared brighter than the one preceding it, though only marginally. The clouds at least kept to themselves on their eastward march across the countryside, though the terrain had grown dark with groundwater and an earthy odour clung to the air. It was still no less a refreshing break from the slog and churn of the city.

I helped myself to the cold toast and marmalade set on a tray outside my door and made a mental reminder to thank whoever had left it. I had not heard a knock, or perhaps I had slept so heavily while dreaming of the chimera pacing in its cage that I had altogether missed it. I did not eat my breakfast, I must add. The bread had turned green at the corner and there was an unpleasant film in the marmalade pot that I did not fancy the look of. The milk was a little sour, but the tea and sugar were palatable. I figured why the little inn no longer boasted the same custom it did in its prime, but I did not openly complain. Not out of good-nature, might I assure you, but because I could not find any member of staff in the entire establishment to complain to.

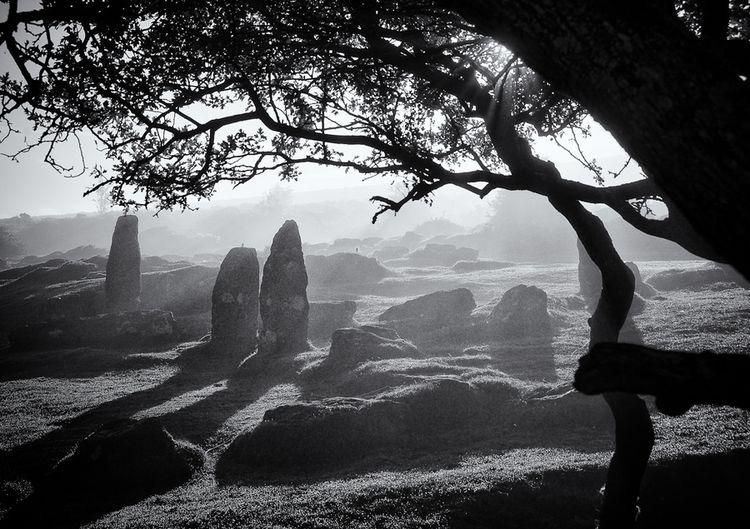

Short of searching for their secret smoking room, I instead redressed appropriately for the outdoors and set on up the hill. Beardown Tor, the locals called it. The climb is none too taxing, but I still found myself lost for breath at the sheer breadth of the moors. The score of mounds and hollows exceed counting in a single day. Its brochure beauty aside, there is something else that local texts fail to describe: the presence of the place. It was if... dare I speak of it... I was not alone. I could not shake the feeling that I had ascended the hills with some unseen companion, of whom I could feel bearing down on my shoulders if I didn't keep moving.

And then there are the monoliths. Great contorted claws of grey rock standing upright at nine, ten, eleven feet, or more! I could not tell you why they were there, what purpose they served, or which mesolithic population erected them, but it is as if they stand sentinel to some ritualistic importance to the place, to which I am uninitiated. I wish one day to revisit them with you, dear, so you might see them. Perhaps when the summer comes around again you and I will find the means and funds to venture farther than Whitechapel.

And yes, I did touch the stones. Though with nothing physically holding me back, I still could not depart from the idea that my unseen watcher scowled as I ran my fingertips over the undressed granite. And... Perhaps I should not write this in the middle of the night when the imagination often runs wild, but the way the winds atop the hills sometimes catch the monoliths, I could have sworn it sounded like voices.

Sometime around early afternoon I doubled back to the woodland Hallenbeck had described in his written correspondences with me. He'd headed out to Wistman's Wood, he'd said, but I had not heard much else from him since I quit his grisly pursuits. It was only when old Emory's boy shared with me the news of his death that I found the circumstances queer. If you recall a time not so long ago during Emory Jr's last visit, I had ushered you away into another room when my colleague began speaking in hushed tones. You asked me afterwards what manner of discussion had followed after I insisted you leave, but I was not honest with you, my love, and I'm sorry.

It had been a Dutch colleague of Hallenbeck's, an amatuer athropologist by the name of Rudolf Haas, who found our missing friend dead in Wistman's Woods. I will not go into detail of the state in which he was found, lest I cause you any upset, but the man had been found impaled on a tree branch high above the earth, with no means to explain how he got there. More curiously still, the autopsy did not reveal anything to Emory that he could not immediately see, leading him to believe Hallenbeck had indeed died from the injury alone...

But it does not end there. Days later, Emory found Haas dead in precisely the same manner, and his autopsy revealed nothing Emory had not already seen in Hallenbeck. So it was with great trepidation and some amount of deceit that I made the journey to Dartmoor before the snowfall bars entry to the little wood on the moors.

I visited Dartmoor just as I promised Jacob Emory I would. Local brochures speak at no great length of the place, and though I thought at first it may be for lack of interest, I am now led to believe it a deliberate act not to inspire curiosity. It is an uncanny and bizarre place, my dearest. No larger or more noticeable than a spilt wine drop on my map, but the atmosphere there is suffocating. Everywhere I looked grew twisted oaks, hunched over in cloaks of green moss; their roots exposed like great, coiled boas. The fog there is dense and earthy, as if the forest breathes.

My intention was not to stay for long, but I found myself ducking under low-hanging limb after low-hanging limb for hours. It's safe to say I was ill-prepared without a compass and the cloud cover did not lend me any clues as to the sun's position. I happened upon a few odd stones that helped me find my way eventually. I knew, at least, that I was going in circles, as I had passed the squat boulder with the eye carving three times. Curiously, though, I could've sworn the stone changed direction, as if the eye had been watching me go. Or perhaps it was some trick of the shadows, or merely my imagination. I favour the latter – after a while, the marbled terrain of green and grey in that forest is sure to conjure patterns that are not truly there.

Or that is what I keep telling myself. Surely it must have been the same phenomenon when I thought I saw that body hanging there.

Worry not from these ramblings, dearest. I maintain that I was still not as well rested as I would have liked from the journey and even less well fed after breakfast. Perhaps it is merely an upset stomach on sour milk that disorientated me and meant I once again lost track of the hours. It was long past dark before I finally made my descent of Beardown Tor, rather annoyed with myself that I had managed to do exactly what I had so strongly tried to avoid.

Yours, with love.

October 16th 1887

With the nights marshalling in so swiftly here and the frost beginning to creep up the window panes, I cannot help but feel drawn back to those Christmas Eves around the fireplace when my father would tell me and my sisters ghost stories. He reserved his best ones specifically for that night. I don't think I ever told you my favourites, but the first he called The Mufflered Man, and the second was a story passed down from his own father called The Voice. One day I will tell them to you, but for now it seems I have a third that might rival my father's own storytelling, were he still alive.

I wrote last time about my experience in Wistman's Wood and decided that pursuing the local lore might be a worthwhile idea. I woke late again – my love, do remind me to leave my pocket watch with the clocksmith when I return – and found my breakfast once again left outside my door. I still have not seen any cooks, maids, or even the owner. My only real acquaintance here so far as been Edmund, the driver, who sorted my suitcase and key.

I have not heard any other guests, either. No snoring, no chattering, no creaks in the floorboards. Not so much smelt the faintest whiff of cigarette smoke besides my own. It could be that I am the only guest. It is out of season, after all, and had the Wych Elm not been the last available inn at this time of year my next choice of lodging might have meant me encroaching on the nearest family farm. But I can't help but remark to myself now and again that this little inn on the hill is strange. Strange in its mysterious workings, its ghost staff, and how it seems time does not pass here the same way it does in London. And yet, in my total isolation, there is a presence I cannot shake. When I stood once again at my window to gaze out upon the moors, watching as the long shadows of morning revolved around those curious standing stones, I noticed an odd hue to the air. It was the tinge of gold one might associate with a snowstorm, and the surrounding atmosphere seemed lethargic with it.

For the first time since my arrival I took the opportunity to hunt down some reading material on the place. I did not find much – only an old, paperback travel brochure broadly covering the whole of the Dartmoor area – but it at least described Wistman's Wood in a mite more detail than the corner paragraph of the South-West Holidays pamphlet I had brought with me from London.

My dear, what I read in that old brochure chilled me. It was as if I was a young boy again sat before my father around the fireplace, listening to ghost stories on Christmas Eve. Even the strange gold glow did not seem so out of place as I absorbed the words on those pages. Just know that I am not the first to feel unease around those standing stones out on the moors.

Nor was Hallenbeck the first victim to be found impaled high on a tree limb.

I did not read further. Not because I couldn't stomach the tale, but because with each line I read aloud the more I sensed 'others' listening; edging closer to me in every direction as if I stood in a crowd only I could not see. I cannot say I fancied staying in the inn any longer than I must. And if nothing else, I must find somebody to speak to.

I shall continue on in time. I promised Emory I would find out who killed Hallenbeck and why. I ask myself daily: who could be so strong as to toss a full-grown man up into the boughs? What manner of supernatural force must it have taken to impale a person from stomach to spine on the blunt limbs of an ancient tree? I did not see the carnage for myself, my dear, and at first I took Emory's words as mere drunken fancy. I have seen how his hand shakes when he holds a scalpel, though he thinks me no wiser. But the more I piece together this place and feel its energy as he did, the more I understood why Hallenbeck wrote in his letters how he grew both so afraid and attracted to the place that he could neither face leaving it nor staying another night.

I must find another person out here. A maid... anybody. I must know more about the wood and the stones, and, more importantly, why curious wanderers seldom return. Might it be my own awareness that frightens me? Might it be there is no spiritual presence here after all and my own loneliness encumbers me, whispering uncertainties in my ear? I hope it is so, my dearest, but in truth it is not the kind of company I wish to acquaint myself with.

Come morning I will rise before the sun and wait for the maid who delivers my breakfast. I need to speak with her. How am I to pursue Haas' and Hallenbeck's deaths in the woods when there is a fair chance I may not return this time too?

It is going to be a long night.

Yours, with love.

October 17th 1887

In the hours between brief periods of sleep, I had time to reflect on the sins I have committed. In the past when I have doubted my morality, you were there to quieten me. You offered me the warmth of your hand and said something to make me smile, as you so often do with that honied tongue you reserve only for me. Your love for me through this arrangement has not waned, and I quite admire your strength for standing by a man like me. It cannot be easy loving any son of my father's, nor is it easy being involuntarily associated with names like Hallenbeck and Emory. But try as you might to comfort me, you also do not understand that silencing my sins has not been good for either of us.

You tell me I am not the man Hallenbeck made me... that I am not his Jack. You are the only one in Whitechapel who knows me by my real name and you remind me of it when you whisper it softly in my ear at night. I know why you do it. But being Jack is a facet of my character that I cannot pretend isn't there. Hallenbeck did not force me into watching him mutilate the dead for his experiments. I was not kept prisoner in his laboratory by ball and chain. I fear there is a dark side of me that is open to such morbid curiosity, and, though you must never tell another soul, I was somewhat relieved when Emory Jr gave me the grave news. For a moment I thought I might at last be truly free, though I was not the only one to notice there was no saddened quiver in Emory's voice when he spoke of Hallenbeck's death either.

But even now when he is dead and lies face up on Emory's table with his bowels exposed and his lips receding over his teeth, I still feel the weight of his influence over me. I fear the dreams of Hallenbeck's chimera will only continue. Is that truly why I came here to Dartmoor? Is it mourning that drives me to search for his killer, or is it mere indulgence?

My wakefulness had been for nothing, my love, except for wishing your body close to mine, for the maid did not deliver a tray to my door this morning. A few times I thought I heard a knock, only to realise after I opened the door to an empty corridor that it might have been the old structure creaking instead. I grew more annoyed with every rumble from the pit of my stomach.

Still, as I wandered the inn searching for another living soul, I couldn't help but notice that every door in the place was open. I could have sworn in the previous days they had all remained closed. Locked, even. But I had been up most of the night, dear, and I heard nothing that sounded much like the clunk of a lock or the cries of aged door hinges. I cannot even ascend the stairs at night without fearing the noise will disturb my neighbours.

But I suppose it would be folly to jump to any conclusions. As I searched the downstairs storey I considered it fair to assume that the doors were open for cleaning or airing purposes. It is not uncommon for old lodges to suffer damp, especially after the rains we have had of late. Still, I found it unsettling that I had yet to find anyone around at all.

It is against my better judgement that I once again felt I must search the hills for the answers I sought and finally return home, leaving that lonely shack of an inn for good. After learning of the incidents in the woods, I would not have advised a return journey there even to somebody I would rather see the end of. So why, I asked myself as I pulled on my boots, was I going? Was it the curiosity that my father had bred into me? Or was it some pervasive morbidity that my many hours with Hallenbeck had secured?

What was more... I wrote in brief in a previous letter of the naked corpse I had seen, hanged from a tree limb with its head oddly tilted and a noose around its neck. If I did not know better I'd have to suppose what I saw was a suicide. But so disorientated and distressed was I that I did not entertain turning back and examining it. I had washed my hands of playing master of the dead months ago and told myself instead that I had not seen it. If ever there arises a police enquiry I will hold my silence on the matter.

As I climbed Beardown Tor around noon, it occurred to me that perhaps Emory had been mistaken. How absurd it was that a mere man alone could spear his fellow on a tree limb. Even a group of conspirators could not have built a mechanism to hoist Hallenbeck that high and leave no trace of such a contraption in the moss.

For the first time I considered that Hallenbeck might have taken his own life. That is not to say he impaled himself, my dear. Heavens, no. The man was a butcher, but he would treat even the most minute of scalpel cuts in his own flesh with iodine and bandages right away. No, the man could not stand to see his own blood – I suppose it reminded him too much of his own mortality. It is not out of the question, after all, that Emory had been drunk when Haas told him what had transpired. He is not known to lie, but if his abuse of the bottle (and I speak not only of alcohol, as he is well acquainted with all manner of tinctures) is anything to go by, it is clear the man is quite easily misled. Was Hallenbeck truly impaled on the tree, or was he merely hanging?

The power of language may make a fool of us all, my love. How typical it is of Emory in his stupors to misinterpret Haas. Or perhaps it was the Dutchman's English that led to this mistake. I ask myself which is more probable: a supernatural force able to skewer a man twelve feet in the air, or a terrified man whose grasp of our native tongue is not one to brag about, explaining what he saw to another who was born with a crystal tumbler in his hand?

When at last I reached the edge of Wistman's Wood, I had already decided Hallenbeck had committed suicide. I retraced yesterday's steps as best I could – ducking under the same moss-cloaked branches, hopping across the river running through the heart of the wood, even counting the oddly carved stones as I went. I took the path I imagined Hallenbeck might have taken in his final moments; he was not one to turn his cheek to risks, even in his old age. It would be his curiosity that drove him in that last hour of his life. Perhaps he had always wished to visit the moors. After all, many noted his singular connection with nature at its most macabre, and I had never encountered a wood so ghastly. It fit. And so did the decision to take his own life.

You may be alarmed to hear it, but there has not been a week gone by since I formally acquainted with the man that I have not considered the same. The few months since we argued over my departure have not fared much kinder, but because of that, and for many other reasons, I thank you for being in my life. Hallenbeck, however, died never knowing the love of another person. How could he live with himself after all those years? I thought him to be married to his work, but perhaps I did not know him well enough, because even with all my lateral thinking I could not get used to the idea that he'd hanged himself.

And it all changed when I found the bodies.

Hundreds of them. Nooses tight around their necks, swaying in the wind, mouths agape. Limbs and entrails strewn across the moss. Entire bodies impaled high on twisted branches, bent and broken like discarded dolls. Bones that had been there so long the trees had grown around them... and the stench... God help me. I'd stumbled upon an entire grove of corpses.

My darling, I fled so fast I hardly remember the path I took, but the woods only grew worse the more I got lost. I slipped on rocks slick and stained with old blood, coming away with fresh grazes. I snagged my cloak on wooden claws reaching out to grab me, yanking my hair from its fasten. It did not matter where I turned, the corpsewood pursued me, always in the next clearing. Dead eyes followed me as I stumbled over upturned roots. Tortured moans rattled through dead leaves over the sound of my own panting.

I could have sworn from the corner of my vision that the terrain contorted more and more into the familiar shapes of the human form. Twigs stretched out into hooked fingers. Rocky hollows rounded into eye sockets. Red, bloodied water splashed up the inseam of my trousers as I dashed across the river once more.

It was already nightfall when I at last collapsed on the edge of the forest. I could not explain the accelerated passage of time either. I was all too relieved to feel the cool, dewy grass on my face as I collapsed to my knees to sob. No, I am not so ashamed of my reaction that will omit this part to you. What I saw in amongst those contorted, ancient trees will be a vision I may well take to my grave. I pity any others like me who have seen it or merely imagined it. Or perhaps that is why they wander back into the woods to join the dead ones...

I am once again alone at the Wych Elm Inn, my love, but I will not sleep tonight. My nighttime view of the forest from my window now sends a shiver crawling along my skin. I am cold to the bone and my handwriting is shaky, but for now I'm safe and sheltered, and the dead ones will remain far away so long as I do not let my eyes rest.

I am returning to Whitechapel tomorrow at dawn. If I have to walk to the nearest town, so be it. I will not stay another night on these moors. Hallenbeck be damned. Whatever killed him will remain unfound.

To Hell with that unholy place!

Yours, with love.

Date Unknown

My dearest, I first asked of you to remember the tale of the wolf and the lamb. How the wolf justified eating the lamb using whatever distorted reasoning necessary. I wrote to you that I am both the lamb and the wolf, as was Hallenbeck's first monstrosity – the monstrosity that birthed Jack at the tender age of eight.

We have not seen each other in many months, my love. I know I broke your heart after I did not return to you from Dartmoor. I held onto these letters hoping you would read them and understand why I did what I did to those women, but you have to understand that the night I saw the dead ones was not the end of my terror.

I know you have read the papers – checked each day in hopes of learning your lover has been found. But instead you read only of the dreadful crimes I have committed and of the frauds who take credit for their infamy. I am disgusted. A kidney. How could they think I would be so arrogant? My own torment is not to be warped into some sensationalist hyperbole. Do they think I do this for pleasure? For thrills?

Deep down you fear it is me, but you will not say. Now that Hallenbeck, Haas and my father have departed this world, I am the only one left known to mutilate the dead in the way of their practice. Emory knows, but my secret is safe with him. He has become so unhinged and so dependent on the bottle now that my brilliant friend seems unable to keep his sentences together anymore. It was sad to see him that way, but I sympathise. He drinks to mute the presence that followed him out of Wistman's Wood when he found Haas dead. He is a slave to whatever tinctures mute the voice that tells him, 'he who escapes the woods must return to the dead ones'.

My dear, I worry you think this only a story. One born of delusion, fear and guilt. What I did to those five women is not the product of malice, but of self preservation. I have brought with me some unseen horror to Whitechapel and the only means of silencing its whisper on the breeze, a breath on the cusp of hearing, is to surround it with death. It is there the forest's evil lingers for a time, but it is not enough to rid myself of this curse. How many vagrants and whores must I slaughter to be free of it? To sleep at night without visions of hollow faces haunting my dreams? How long until time once again passes as it once did, and I can truly see the people passing me in the street, not just their shadows?

And to return to you, my sweetest. You who have been so resilient and understanding. I wish only to hold you close, but these killings cannot continue. I know now why Hallenbeck surrounded himself in his work. The unending cycle of death and decay that surrounded his experiments kept the forest's call at bay. But he was stronger than I. He was seventy-six before he returned to the forest to accept a calling that had plagued him since he first set foot there, and blindly I followed him into the same fate. I do not know how much longer I can go on like this. With innocent life I end, my real name slips away.

But I curse the old man for leading me to the moors in the first place. Do you remember that day he and I argued about the future of his projects? I left that day wanting no further affiliation with his questionable deeds and he told me he would find a way to convince me to continue his path. Neither you nor I knew what he meant at the time... but he has won.

It is the lamb and the wolf of his own design.

---

Finn Arlett (FinnyH) is a passionate Wattpad Ambassador, working behind the scenes with big profiles such as Paranormal, LGBTQ+, Adventure, Historical, and JustWriteIt. He is also a featured, multi award-winning author both on and off Wattpad and has been published by Henshaw Press, debuting with his chilling piece of literary fiction: "The Platform". His horror novella "The Folveshch" has made its way into six movie promotions reading lists on Wattpad in 2015/16.

His short story "Conkers" was also recognised by Wattpad and Disney as a Top 10 entry in the Beauty and the Beast competition. Known primarily for his historical horror stories, his work has been described as "brilliant", "classic", "twisted", and "a terrific departure from the norms of horror convention".

Besides pursuing a love for writing anything remotely creepy, he is a character artist, cover designer, composer, pianist, and massive space nerd (examples of which are all over his profile). He's also pretty accomplished at demolishing red velvet cake. He lives in the United Kingdom with his dopey but loveable best friend: a sock-stealing spaniel named Alfie.

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: Truyen247.Pro