Part vi. Drafting a Developed Character

Now it's time to take all your ideas about your protagonist, your main characters, and your minor characters and channel them into the writing of your novel. You'll need to show your readers who your characters really are.

First Impressions

Every character in your novel has that first appearance on the page. As in life, first impressions matter. You want to stamp into your reader's brain your own sense of who each character is—their emotional presence as much as the details of their appearance and wardrobe.

Whatever you decide your protagonist looks like, it's a good idea to communicate that to the reader within the first ten pages or so; otherwise readers will busily create their own image of your character and it may not be at all what you want them to see.

For example, from "Fantasy in Death," Nora Roberts, writing as J. D. Robb, introduces Bart Minnock, who will soon be murdered by his holographic video game:

While swords of lightning slashed and stabbed murderously across the scarred shield of sky, Bart Minnock whistled his way home for the last time. Despite the battering rain, Bart's mood bounced along with his cheerful tune as he shot his doorman a snappy salute.

"Howzit going, Mr. Minnock?"

"It's going up, Jackie. Going way uptown."

"This rain could do the same, if you ask me."

"What rain?" With a laugh, Bart sloshed his way in soaked skids to the elevator.

Notice how efficient Roberts introduces this character with only a meager physical description. And yet, from his dialogue and behavior, the reader has a strong feeling for this upbeat, goofy guy who bounces along, whistling, completely oblivious to the literal storm raging around him. The little detail of the doorman shows us Bart Minnock is a wealthy city dweller. Notice, too, that the character's full name is right there, the moment he first appears on the page.

A little further on in Robert's novel, there's another character introduction. We meet CeeCee. Think about how this one feels different from the previous example.

Eve found CeeCee in the media room on the first level. A pretty blond with an explosion of curls, she sat in one of the roomy chairs. It dwarfed her, even with her legs tucked up, and her hands clasped in her lap. Her eyes—big, bright, and blue—were red-rimmed, puffy, and still carried the glassiness of shock.

Did you notice that this introduction of CeeCee contains much more physical detail? It's written to that the reader can really see CeeCee with her "explosion of curls" sitting in a chair that "dwarfed her," her eyes red-rimmed and glassy with shock (she just learned of Bart's demise).

Showing the Reader a Viewpoint Character

One of the special challenges in writing a novel is giving the reader a sense of what your protagonist looks like, particularly when the whole novel is written from that character's viewpoint.

With the viewpoint anchored in the character's head, it simply wouldn't feel natural for the character to say, "I have red hair and rectangular-rimmed glasses..."

The one time you can get away with this, however, is if your character speaks directly to the reader. If you have your protagonist speak directly to the reader, make sure to stay consistent in that communication with the protagonist and the reader throughout the entire novel. If you have the protagonist only speak directly to the reader once or twice (which is quite common in Wattpad stories) then it seems unnatural and amateur.

So how does a viewpoint character convey her own appearance to the reader? It's become a cliché to have the character look in the mirror, or notice her own reflection in a window and describe what she sees. However, many writers to just that and make it work. But there are other ways.

Here's an example of a viewpoint character conveying what she looks like to the reader:

He checked her out, "You look comfy."

Sam looked down, taking in her matted furry slippers, sweatpants, and an oversized Winnie the Pooh sweater. Her face grew warm, and she tried to run her fingers through the tangles in her ash brown hair.

In this example, Sam is a viewpoint character who looks down at what she's wearing in response to another character's remark about her appearance. Of course, the reader has no idea what Sam's face looks like or her eyes color, whether she's pretty or plain, tall or short, but we do get a sense of who she is from the few details provided.

Conveying a Character with Telling Details

In describing a character, think about the one or two key details that say it all. Normally trivia like height and hair color and eye color fail miserably in expressing a character's appearance.

Here's an example from Fern Michaels's "Weekend Warrior." Notice the telling details Michaels pricks to describe her character, Charles Martin. As you read the brief excerpt, think about which of the details are most striking.

Charles Martin was a tall man with clear crystal blue eyes and a shock of white hair that was thick and full. Once he'd been heavier, but this past year had taken a toll on him, too. She noticed the tremor in his hand when he handed her a cup of coffee.

Though the "crystal clear blue eyes" and the "shock of white hair" give the reader a visual image of a vigorous man, the contrasting hand tremor conveys to the reader even more information: though he seems vigorous, he's been through some trauma or illness. This is a telling detail—it intrigues, and we'll have to read on to find out what it's all about.

Here are a few examples of telling details:

• The character wears an expensive suite with a button missing.

• The character wears a tattered but once glorious bridal gown.

• The character arrives at a cocktail party in jeans, cowboy boots, and a ZZ Top tshirt.

• The character is wearing wristwatches on both arms.

• The character has beautifully manicured nails but her fingertips are calloused.

• The character wears steel-toed construction boots and his fingernails are manicured.

A tip: Try not to over-describe your characters or you'll bury the telling detail.

Here is another example, John Berendt introduces the character Chablis, when she appears for the first time in the novel "Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil." As you read it, think about how this description conveys so much more than Chablis' appearance.

She was wearing a loose white cotton blouse, jeans, and white tennis sneakers. Her hair was short, and her skin was a smooth milk chocolate. Her eyes were large and expressive, all the more because they were staring straight at mine. She had both hands on her hips and a sassy half-smile on her face as if she had been waiting for me.

Berendt has chosen the telling details carefully. His description is vivid and conveys not only Chablis' physical presence but also her attitude. Berendt piles on the detail to achieve this, and it could have read like a laundry list. Instead, the character nearly pops right off the page.

Characters Are What They Do

You've probably heard, over and over, that fiction writers need to "show not tell." I've even mentioned it in this book. One of the best ways to show a character to the reader is by putting her on the page and letting her perform, especially when the character does something that's surprising.

You can give your character gestures or habits that convey her inner character. A character's actions—what she does or doesn't do—also show your reader what the character is made of.

Telling Gestures and Habits

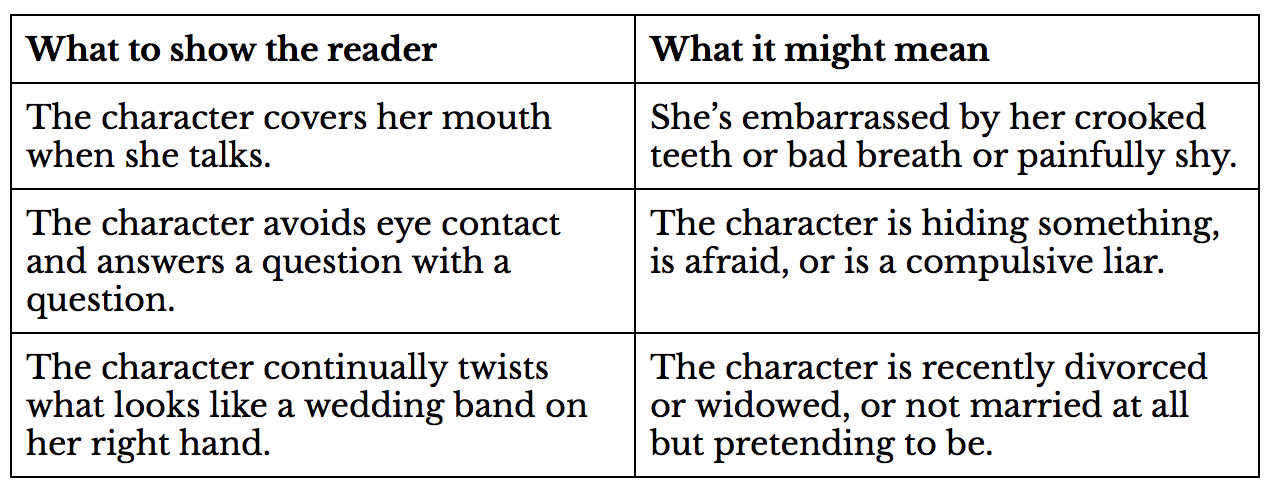

Characteristic gestures or habits, chosen carefully, can show the reader without having to explain. The gesture or habit will suggest several possible explanations. Through your storytelling, you'll show the reader which it is.

Be beware of tells—gestures and habits that have been used a million times before by authors to telegraph information. Overused habits or gestures can feel like annoying, and possibly clichéd tics.

Showing Character Through Behavior

Writing is all about making choices. On each page, you have to decide, "What is this character going to do now?" Support, for example, your character walks into a department store. What does she do?

• Head for the sales rack?

• Browse designer jewelry and slip on a ring that she forgets to take off?

• Mix a bunch of size-two dresses in with the size twelves?

• Try on every pair of Michael Kor shoes in her size?

• Get weepy as she browses baby items?

• Plant a bomb?

• Set a fire?

• Crouch behind a potted plant and watch one particular sales person?

If you've thought through your plot and have an outline or synopsis written, then you'll have a pretty good idea what this character will do.

But support you start writing the scene and the character does something that surprises you. Authors talk about a character who "takes over." When it happens to you, welcome it. Try to go with it, for at least a few more pages. It might turn out to be a terrific plot twist, and what surprises you will be sure to surprise your readers, too.

Characters and Their Voices

Another way to show your character is through voice. All characters have spoken dialogue; viewpoint characters have internal dialogue, too. Lace that dialogue with attitude and you can show your character's personality.

Take, for example, something as simple as the way that your character greets another character. Is it "Howdy," or "Yo," or "Pleased to make your acquaintance?" Is it stony silence when the other character is his wife?

You can show the relationship between characters, perhaps even unfinished business between the, by the way the greet one another. "Hi there," conveys a whole different feeling from "So?"

Internal Dialogue

One of the strongest tools for showing character is internal dialogue. Only a point-of-view character gets to show the reader his thought process, communicating why he does what he does. Internal dialogue is what's going on in your point-of-view character's head as he muses, argues with himself, observes, makes decisions, and so on.

Here's an example of internal dialogue from Rebecca Wells' "Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood." In this short excerpt, main character Sidda opens her mother's scrapbook and, in the process, discovers the novel's eponymous "secrets."

The first thing Sidda did was to smell the leather. Then she held the album to her chest and hugged it. She wasn't sure exactly why, but it occurred to her that what she wanted to do, what she needed to do, was light a candle.

A few paragraphs later, after Sidda has looked at a few pages:

She wanted to devour the album, to crawl into it like a hungry child and take everything she needed. This raw desire made her feel dizzy.

Wells does so much more than merely show Sidda's thoughts. She shows the reader Sidda's overwhelming sensations, her reverence in this moment, as well as her confusion about what it all means.

Showing Character by Revealing Backstory

Just as real people are shaped by past experiences, a character's fictional past (also known as backstory) influences how that character thinks, looks, and behaves in the present.

Suppose you are writing about a character who is terrified of snakes or unable to commit to a relationship, or is an obsessive workaholic. If you've done your homework and developed a backstory for that character, then you know exactly why she is the way she is.

That snake phobia may have resulted when her brother put a pet boa constrictor on her bed when she was six. Maybe she can't commit because of how traumatic it was for her to watch her mother fall apart after her father abandoned the family. Or she may be a workaholic because she's afraid to slow down enough to grieve for her dead husband.

One of the most frequent mistakes authors make is to lay out the character's backstory in the beginning of the novel. They go on and on, dumping the backstory in the reader's lap, telling how the character grew up in a broken home and how she was an alcoholic who inadvertently killed her child in a car accident, and, and, and...

A hint: How much backstory your reader will tolerate is in direct proportion to how much forward momentum your novel has achieved.

It turns out that the reader probably doesn't need to know any of this. At least not yet. Backstory about characters readers don't yet care about is boring. So, first you have to make the reader care about the character, then you can layer in all the backstory you want.

So when it's time to tell the backstory, how do you do it? Not all at once. There are many different ways to convey backstory without writing a clunky backstory dump. Bits and pieces can be layered in as the story moves forward; the more important chunks of backstory can be told in flashbacks.

Backstory Layered in Internal Dialogue

Internal dialogue is an effective technique for slipping the reader information about a character's backstory. Here are a few examples:

• There was Bruce. I hadn't seen him for months, not since his wife disappeared.

• The tiny gravestones reminded Sarah of her own stillborn child; her husband had insisted that they whisk his little body away before she even had a chance to say good-bye.

• Jane wanted to tell him she loved him. Really she did. But something about him reminded her of Daniel, and what had happened the last time she'd let down her guard.

In each of these examples, the viewpoint character conveys a little flash of memory, triggered by an object or event in the present.

Backstory is often best layered in. So you might write just a quick reference, like these, to some event in the past And then later add more detail in another quick flashback, and later add in even more until the full story emerges.

Backstory Conveyed in Dialogue

Another simple way to convey information about your characters' pasts is through spoken dialogue. Here are a few simple examples:

• "Bruce! I haven't seen you in so long, not since the funeral." I paused, wondering why on earth I'd blurted that out. But he didn't seem bothered. "I'm sorry. I know I should have called."

• "Yes, I had a child," Sarah said. "Once. She was two pounds, two ounces, and we named her Amanda." Her vision blurred. "I never even got to hold her."

• "I just couldn't say it," Jane said later to Miranda as they sat in Miranda's kitchen eating fresh-baked chocolate chip cookies. "I kept thinking about Daniel, and how he betrayed me that day after I told him I loved him."

When the opportunity arises in the story and dialogue like this feels natural, then it's an easy and straightforward way to convey backstory. But beware of overdoing it.

Backstory Conveyed with Props

Fill the fictional world your characters inhabit with props. Use them to suggest your characters' backstories. Consider a character's bedroom. Here are just a few items it might contain that will give you a chance to hint to the reader something about your character's past:

• A wedding picture with the glass broken.

• A colorful but fraying afghan crocheted by the character's grandmother.

• A bulletin board with curling yellowed clippings tacked to it.

• A photo booth strip of pictures of the character mugging for the camera with a beautiful young woman.

• Bookshelves loaded with self-help books like "When Am I Going to be Happy?" and "Women Who Love Too Much."

• A collection of guns in a wall-mounted display case with one of the guns missing.

Each of these props suggest a backstory. When your character looks at that wedding picture, or adds another clipping to the bulletin board, you get a natural opportunity to convey backstory as the prop triggers a thought or a bit of dialogue about the past.

Backstory Conveyed with a Flashback

There will be big, important parts of the backstory that you may want to dramatize rather than downgrade to internal or spoken dialogue. You can handle these by writing the scene as a flashback.

Trigger the memory with something in the present, then segue into the past and write a scene within the scene, dramatizing the past event, staying in the viewpoint of the character who remembers. Then segue back and continue.

Character Checklist

When you put a character on the page for the first time, you want him to make an impression.

Here's a handy checklist by Hallie Ephron to make sure you've made that first impression count:

• Have you established the basics about the character —name and gender?

• Is the character's relationship to the narrator clear?

• Have you avoided character clichés?

• Have you given the reader enough information to visualize the character? Did you allow telling details to show?

• Have you shown your reader this character's mood and attitude?

• Did you suggest the character's backstory but save the details for later?

Over time, as the novel continues, you will add nuance, detail, backstory, and allow your character to show himself through his actions, thoughts, and dialogue. Short flashbacks can come after the character is fully introduced, and longer flashbacks once your story has established a good amount of forward momentum.

Please remember to vote if you've learned something valuable and new!

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: Truyen247.Pro