Part v. Editing

When you've made the major revisions to your novel and you are satisfied with the way the plot flows and twists, with the climax and resolution, and when the characters and settings feel as vibrant and believable as you can make them, it's time to sweat the small stuff. You'll need to polish every scene, every paragraph, every sentence so your manuscript will be as perfect as it has to be in order to pass with an agent or professional editor.

Fine Tuning

When you've addressed all the big issues in your manuscript, given it to still another batch of advanced readers to confirm that your plot and characters are working, then it's time to pull out the microscope and examine it up close.

First step: Print out the manuscript. While some final polishing can be done on-screen, reading and editing directly in the digital file, there's no substitute for the perspective that printed pages give you. Somehow, errors that slip past on the computer screen seem to pop off the printed pages.

Expect to go through your manuscript at least three times to get the job done.

Strong Starts and Finishes

First impressions and final impressions are what readers notice most. So lavish some special editing attention on all these starts and finishes in your manuscript:

• Make the first line, the first paragraph, and the first scene as strong as you can make them.

• Introduce each setting vividly.

• Make each main character's first appearance memorable, establishing that character's physical presence with a few telling details as well as the character's voice.

• Pay special attention to the first and last paragraphs of each scene.

• Make the last page, the last paragraph, and the last line as strong as it can be; leave the reader with something to think about.

Tighten Each Scene

Read each scene through and assess whether it delivers everything that a scene should. A flabby beginning should be tightened. If it starts too early, cut to where things get interesting. Floating characters need to be anchored in time and place. An ending that dribbles off should be trimmed. If there's no conflict in the scene, look for opportunities to insert some.

And most of all, make sure that your novel needs every single scene that's in it. If you can cut a scene and the story won't suffer, cut it!

Here's a checklist of things to look for in each scene:

• Strong start: Does it engage the reader right away; are you starting it as late as possible?

• Clear orientation: Is it clear to the reader, within a paragraph or two, where and when the scene takes place and who is there?

• Conflict: Every scene should have some tension or conflict; at least one character should feel off balance.

• Arc: From beginning to end, something should change in the course of each scene, even if it's nothing more than a character's emotional state.

• Strong finish: Does it end strong and as early as possible, or does it just dribble off?

Tweak the Chapter Breaks

When your scenes are as tight and compelling as you can make them, then examine how you've grouped them into chapters. Chapters can be long or short. Use the placement of chapter breaks to add to the momentum you are trying to create in the story.

Where you want momentum to build and the reader to keep turning pages, break a chapter in the middle of scenes at a cliffhanger moment. Where your storytelling is more leisurely, then break the chapter at natural scene breaks.

Pump Up Dialogue

One of the best ways to tell whether the dialogue in your manuscript is working is to read it aloud to yourself. The ear is much better than the eye at picking out clunky words and phrases. As you read just the bits within the quotation marks aloud, think about whether the dialogue conveys the personality and emotion of the speaker. If not, tweak the word choice and sentence structure so that it does.

Here's a simple example. Imagine all the different ways a character can greet another character, and what impact each greeting would have on the reader's understanding of the relationship between the two characters.

• "Hello."

• "How do you do?"

• "Hey, you. What's up?"

• "Yo, bro."

• "Oh, it's you again."

• "Hey, you with that face, yeah you, I'm talkin' to you!"

Maybe the simple, "Hello," is all you need. But make that be a conscious choice.

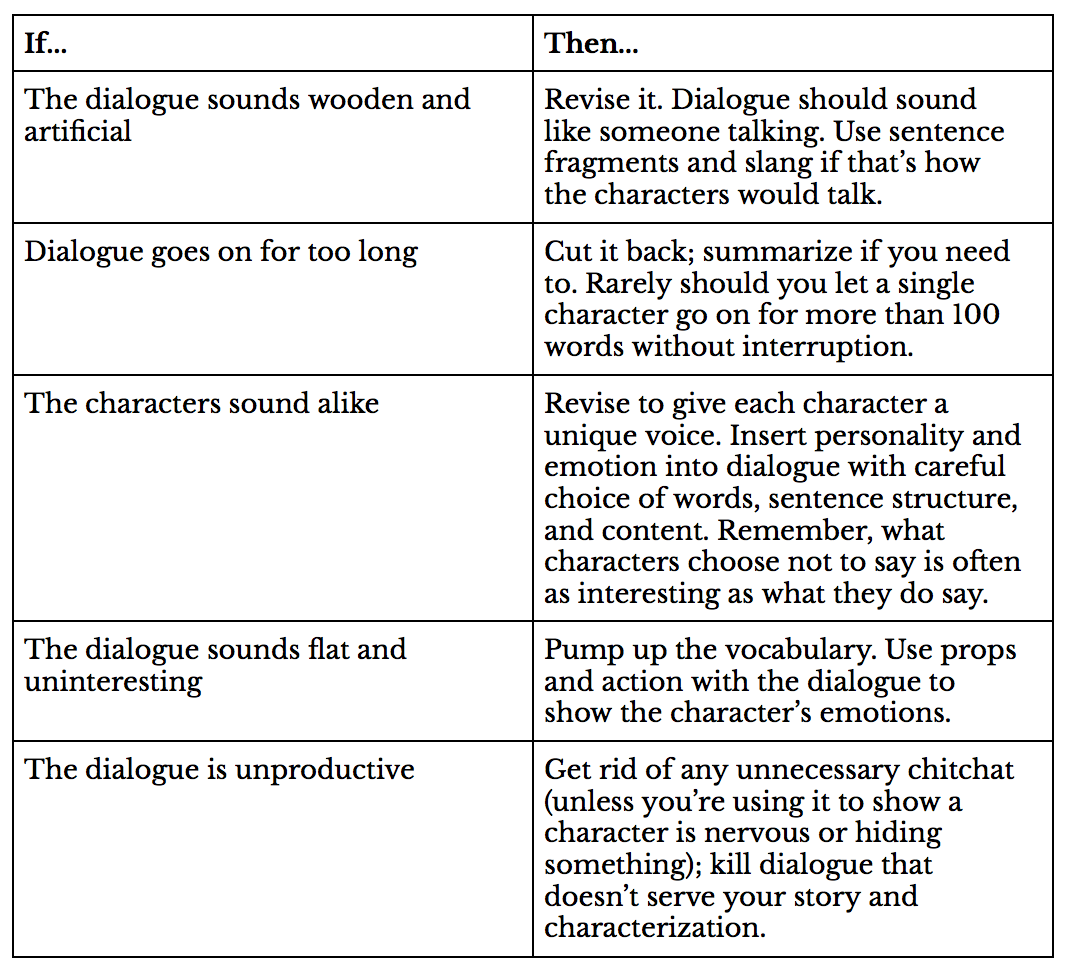

Here are some more problems you might find with the dialogue you've written.

Pump Up Verbs

Verbs are the workhorses of fiction. Throughout the manuscript pay special attention to your verb choices. Make sure you're using the best one you can to convey the action and emotion of the character and the moment.

Suppose you've written this:

Stephen got out of his car and went to the front door.

Got. Went. These are blah verbs, lazy verbs. What if Stephen is a man on a mission? It would be much better to say:

Stephen stepped from his car and marched up the front walk.

There's nothing fancy or literary about stepped and marched, but they express determination much better than got and went.

Suppose Stephen is coming home drunk from a debauched overnight. Just tweaking the verbs can convey that.

Stephen heaved himself from his car and stumbled up the front walk.

On the other hand, suppose Stephen's life depends on him getting into that house fast.

Stephen leaped from his car and raced up the front walk.

Only you know what you're trying to convey. Pick the verbs that best show the action and attitude you're aiming for. Look out for those easy but overused ways to show emotion. If your characters are constantly responding by smiling, frowning, shrugging, nodding, or shaking their heads, get in there and write it with more nuance.

Examine Distancing Verbs

There are a number of verbs that keep the reader at arm's length from the character. Sometimes that is the effect you want as if your character is floating and not quite in the moment. Or remembering something that happened long ago. Or when the narrator is omniscient. But more often you want to go for immediacy.

Here is an example:

She felt a flash of heat sear her face.

A flash of heat seared her face.

Notice how the verb "felt" serves to distance the reader from the character's feelings. By eliminating it and writing the sentence more directly, what she is experiencing becomes more palpable and powerful to the reader.

Here's another example:

She wondered if Ralph was ever going home.

Was Ralph ever going home?

Here, the verb "wondered" distances the reader. Translating the question into a direct thought, coming from the head of the viewpoint character, makes it stronger.

Here are some distancing verbs to watch out for and to consider eliminating:

• Felt

• Wondered

• Thought

• Realized

• Noticed

• Knew

• Saw

• Decided

Examine those ing verbs

There will be times when you want to write using what grammarians call the past progressive tense.

He was racing to the car...

But use it only when you want to show that something else was happening during the race: He was racing to the car when he tripped over his own feet and crashed into the gutter. In most instances, it's better to stick to the simple past tense.

He raced to the car.

With the active verb, raced, the sentence feels more direct, the action more active, the feeling more immediate.

You won't want to remove every ing verb from your manuscript. Every time you find one, ask yourself: Would this sentence be stronger using the active form of the verb? If so, revise.

Scrutinize Those ly Adverbs

A whole load of ly adverbs sneak their way into first drafts. Often writers use them to try to pump up bland verbs—walked (quickly), got up (jerkily), moved (painstakingly). But usually, an adverb is just another form of lazy writing—a way to tell the reader something that would be much better shown.

As each adverb comes up, scrutinize it (carefully). Occasionally, you'll want to leave it be. But there are other times when you'll want to delete it and substitute some better writing.

When you find an adverb trying to help one of your verbs, consider taking the following actions:

• Delete the adverb and see if, just maybe, you didn't need it in the first place.

• Consider replacing the adverb/verb combo with a verb that better conveys the action being taken. For instance, walked slowly could be replaced by ambled, drifted, shuffled, staggered, strolled, traipsed, stumbled, or crept along, depending on what exactly you are trying to convey.

• Consider replacing the adverb with more descriptive action. For instance, instead of He walked slowly, you might write He grimaced and held his side as he hunched forward and took one step, then another. Or give the character a prop to show the feeling you are trying to convey.

Rewrite Clichéd Expressions

One writer's literary flourish is another writer's cliché. A manuscript full of them is the sign of an amateur. Go after them ruthlessly, these turns of phrase that have been so overused that they feel trite.

If you have a character who's a pompous windbag, then it's fine to let him spout clichés in his dialogue. But embed them in your narrative and you're the one who comes off looking like a bag of wind.

Clichés often sneak in when you're trying to be smooth or smart. Sometimes, too, when you're tired and just haven't got the energy to reach beyond the cliché. Whenever you come across a clichéd expression in your manuscript, try doing one of these things:

• Replace it with your own fresh image or metaphor.

• Delete the cliché and write something descriptive; for instance, instead of Stephen ate like a pig, you could show the reader the gravy stains on his tie, his open-mouthed chewing, and how he holds his fork in a clenched fist.

Eliminate Redundant Redundancies

Sometimes, writer's repeat themselves. Here are a few examples of repetition compulsion. See if you can spot the overwriting.

• She turned white and backed away from him. "Stay away from me," she said, frightened.

• "He's so big," I said, considering the relative size of the other babies in the nursery, who were all smaller than Nathaniel.

• Linda wanted him to let her show that she could do it. "Give me a chance, would you?" she said.

• "Please stop," he begged.

In the first example, the writer showed how the character blanched and backed away. Her dialogue shows her fear. So it's not necessary to add frightened.

You don't have to spoon-feed readers. If you show a character's desperation, anger, or confusion, you don't need to name it or add an explanation, which would be telling.

Look for Inconsistencies

It's so hard to keep track of all the details in a novel. Is your protagonist's bedroom the first door off the hall or the second? Is her bathroom rug pink or blue? Does she write with her left or right hand? Does traffic on the main street around the fictional corner flow only one way or two?

You may lose track of these kinds of details, but there are plenty of readers who will not. So go through your story looking at the small stuff. Look for inconsistencies and fix them.

Here are some of the examples you might find.

• Discontinuity: Violet stands up and then, two paragraphs later, she stands up again; Violet and Willem toast one another but only one wine glass ends up in the sink; a coat that Violets hangs up when Willem arrives is found folded over the back of a chair the next morning.

• Geographic inaccuracies: A car drives the wrong way down one of Chicago's one-way streets; Violet gets a coffee at Starbucks on a corner where there's really a gas station; Willem drives an hour to get somewhere that's only five minutes away. If you want to play fast and loose with geographic details, it's best to set the novel in a fictional place, but even there, readers will expect things to be consistent.

• Time frame: A scene takes place with a morning alarm clock going off that ends an hour later with car headlights shifting across the bedroom window; it's dark in the parking lot in Los Angeles in July before nine at night; Violet takes a three-hour drive, but there is no sense of time passing.

Character Names

Names are tricky. Suppose you have a character named Lindsay Berlinger. She's an attorney. Her sister calls her LB, her colleagues at work call her Berly, and her friends call her Lindsay. If you refer to her as Lindsay, LB, and Berly in the novel, you create a problem for the reader trying to keep your characters straight. The less attentive among them—and there are lots—will think these are three different characters.

So give your readers a break. Be as consistent as possible about what you call each character. Here are some rules of thumb to follow:

• In the narrative: Suppose that in scene one, you write: Lindsay opened the door. From then on, the narrative should refer to her as Lindsay—not LB, or Berly, or "the attractive attorney."

• In dialogue: In spoken dialogue, you have much more flexibility. Other characters can and should refer to LB by whatever name they would in real life. Her boss or coworker might greet her in the morning "Hey, Berlinger," her son might say "Mommy, can you come here," and her mother might say "Miss Smartypants, what on earth did you think was going to happen?"

Lock Down the Viewpoint

There are few things more distracting to readers, especially those who write or edit fiction, than a sliding viewpoint. The name for it is head hopping.

Here's an example. See if you can find the slide.

Minna was exhausted. There was her friend, Samantha, just getting to the party. She waved to her. Samantha started to wave back, then hesitated, noticing the dark circles under Minna's eyes.

The first three sentences are written from Minna's viewpoint—we get her exhaustion and she sees her friend and waves. Then the viewpoint hops right over to Samantha and we discover that she's noticing Minna's dark circles. Minna wouldn't know that unless she was a mind reader.

Try to avoid allowing your own authorial viewpoint to sneak in, too, as in this example:

Minna should have been warier of her friend because Samantha was about to betray her trust.

Or another example:

Minna didn't realize that Randall was also watching her as she waved to her friend.

Look for point-of-view slips and clean them up. If you're telling the entire story from your protagonist's point-of-view, make sure every scene is written with the protagonist as the narrator. If you're telling the story from multiple points-of-view, the point-of-view character can shift from one scene to the next, but it should never slide around within a scene. Stick to a single narrator in each scene.

Fixing Grammar, Spelling, and Punctuation

"Don't publishers fix grammar and spelling mistakes?" an unpublished writer asks. Of course, they do, but sloppy errors in your manuscript certainly won't impress agents or editors.

You're inviting that person who could help you to conclude that you can't write your way out of paper bag. Your goal should be a manuscript that's grammatically perfect and free of errors in punctuation and spelling before you send it out into the world.

Here are some tasks to get you there:

• Run the spell checker: Your word processing software has a sturdy spell checker and will find and suggest fixes to misspelled words. Of course, it will try to correct any dialect you've included, and it may not recognize technical terms, product names, or slang expressions, but all you have to do is reject the changes you don't want.

• Run the grammar checker: Grammar checkers that come with word processing software can be a pain in the butt, flagging all kinds of "problems" that you'll want to leave as is. For instance, it'll want to fix all your sentence fragments. Dialogue is full of them, as it should be. Run the grammar checker anyway, and skip over those non-problem problems. Along the way, it'll find problems you might otherwise miss—like subject-noun agreement, missing questions marks, double spaces between words, or missing punctuation.

• Read and edit: Read through your manuscript yet again, after you check for grammar and spelling, and find all the errors your word processing software missed. For instance, it may not have caught your use of "there" instead of "their," or "its" instead of "it's." Misspelled proper nouns will have slipped by as well.

• Have someone line edit for you: If you're not great at catching spelling and grammatical errors, give the manuscript to someone who is, but don't give them free rein to make changes in the file; you should be the one to decide which changes to make.

Please vote if you've learned something new!

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: Truyen247.Pro