601 INTERNATIONAL BRIGHT YOUNG THING

INTERNATIONAL BRIGHT YOUNG THING

So living at Jordan's turned out to be like living at Grand Central Station. There was always someone interesting coming or going. Musicians, songwriters, deejays, New York art scene people—it wasn't always clear who was connected to him for actual work and who was just there to hang around. Then again, I suppose making connections is part of the work when you're in the business. The old cliche is "it's not what you know, it's who you know." I'd say it's more like both: you have to know your what, but you have to know the who, too.

Jordan was a connector. He was a match-maker. A people-person. My overwhelming impression of him from when we'd worked on the Moondog Three album together was that he was quiet. Quiet and serious. That impression didn't change after three weeks in New York. Jordan being serious and quiet made people think of him as a "good listener." Not a day went by when someone didn't want his advice about something and to tell their whole tale of woe, whether personal or industry-related or what. Which meant that sometimes I think Jordan didn't actually listen. He'd have the phone on his shoulder and murmur "mm hm" from time to time while he did something else with his hands, like fuss around with MIDI tracks in the computer. But I think it didn't matter: people felt better after using him like a kind of confessor, and at the end he sometimes even dispensed advice which was always supportive.

Then again, Jordan's actual job, in some ways, was to be a "good listener." In the studio he was listening for what was there, and what things could be, trying to bring out the sonic excellence in a performer or a song or an arrangement. And on top of that he was the go-to guy for some record execs when they had a problem artist. Whether that artist was a diva who had gone bride-zilla during recording or a fragile talent who had faltered because of shattered ego or what.

I could see why Mills had gone straight to him when Ziggy had been difficult.

Ziggy was the topic we mostly avoided for the whole first week I was there, partly because we were so busy. We spent a couple of days tacking down rough demos of songs, and then one day Jordan said to me while handing me my noon cup of coffee, "Let's go to the studio today."

"Okay." That was about as much as I could say until the coffee sank in. When it did, I added, "Why?"

"Because I think I have someone who is going to want 'Sex With an Ex' and it'll go down a lot better if the actual showcase reel doesn't have the sound of sirens driving by in the background."

"Okay." That made logical sense. Except it didn't, and I realized that by the time I got to the bottom of the cup. "Wait. 'Sex With an Ex'? Trav, you're kidding. I just tossed that off for fun."

"Exactly," he said, and didn't offer any other explanation.

That's how I learned anything I played, even stuff I was just goofing around on, went into Jordan's auditory memory banks.

So we went to a studio on the fifth floor of a mixed-use building in Tribeca. If you aren't familiar with New York City it's hard to describe what most of the buildings are like. I think most people picture "office buildings" as skyscrapers with wide, gleaming lobbies. But the majority of the buildings are 5-10 stories tall, cramped, with a million different businesses crammed in them. A massage parlor, commercial art studio, insurance agent, religious tract publisher, and pet psychologist were all in the same building with the recording studio. We went up the stairs. The only elevator came off the loading dock in back and was the kind with a cage. I don't mean the gilded-age kind of cage, I mean the industrial ones that open top-to-bottom.

That kind of wet snow was falling that day, that kind that wants to change to rain but doesn't quite manage it. It soaks your shoes, though. When we got upstairs we were sweaty and winded, and I took my sneakers and socks off and put them on the radiator to hopefully dry.

"I know this is just a demo," he said, while I tuned up the Fender, "but I'd like to multi-track it."

"Your wish is my command," I said, non-ironically.

"Cool." He busied himself setting up a mic and screen in the vocal booth, and then fussing around with the drum kit in the corner.

I didn't ask something dumb like You play the drums? since apparently he did.

I don't think it took us more than an hour to nail down "Sex with an Ex." It's not a long song, it's a simple song, and we ended up not needing very many takes. Jordan also played bass, which he laid down while I did a second guitar track.

I should explain something about recording instruments like electric guitars to tape like we were. You can't just take the plug on an electric guitar and, say, plug someone's headphones into it and expect what they're going to hear is what an electric guitar "sounds like." A lot of that sound you expect to hear is created by the effects pedal and the amp. To get that sound on tape what you're recording isn't the sound coming out of the guitar, it's the sound coming out of the amp. So to get it onto tape, that means putting a microphone in front of the amp.

That means, though, that the amp and the mic can be in a soundproof booth, while the guitar and the guitar player and the engineer and whoever else is hanging around, can be at the desk in the control room chatting with each other. None of the sound of the chatting gets onto the recording. This means you can be telling each other things like "Go into the B section here," and "Is this where you want the chorus to come in?"

If you're me, that cuts down the number of takes, since unlike in a live performance, you can be cuing each other. Also unlike a live performance, if you flub something you can stop and pick up again from that spot and you don't have to start over from the beginning.

The last thing we recorded was the vocals. "You want these lyrics written out?" I asked.

"Why?" Trav leaned back and put his feet up on the other chair at the mixing board. "So I can hand them to whoever we're trying to sell the song to? You know lyrics always look stupid written out."

"Oh, you mean I'm singing it?" I couldn't stop myself from taking a glance at the vocal booth.

"It's your song," he pointed out.

"Just checking. You played all the other instruments."

"Except the important one." He waved me toward the booth. "Get in there. You ever been in a vocal booth before?"

"You know I have. You were there when we recording backing tracks for 1989."

"Didn't remember," he said, though he was bullshitting. "Remember, this is just a demo. I mean, make it sound good, but you know, whoever actually records it isn't going to copy your vocal style most likely."

"Good, because I haven't got much of one."

We ended up nailing the vocals in two takes–one really, because we decided we liked the first one better than the second one. I told you it was a simple song.

Ten hours, an order of take-out Chinese, and a couple miles of tape later, we'd laid down three more songs. I didn't have a sense of if that was a lot or a little, but Jordan seemed very satisfied with what we had.

We left the guitars locked up there with plans to return the next day, then dropped by the apartment to change clothes. The snow had stopped and the clubs were open.

We didn't do Limelight that night. Instead we went down to a little queer underground place on Avenue A. I laughed when I realized I'd been there before, but didn't tell Jordan why, and he didn't ask. It was the place I'd talked my way into when I was underage, when I was still in school, that time I'd come to the city with Nomad. This time I looked at the name: Pyramid.

It was evident Jordan was well-known there, and I wasn't surprised when the dancing was interrupted by a stage performance, nor by the fact that Jordan introduced me to the performers afterward, nor when the two of them–one drag queen and one butch guy–came home with us to Jordan's loft and spent the wee hours smoking weed and talking about Art with a capital A.

I know, you were expecting an orgy. Honestly, talking about Art for art's sake was about as decadently indulgent as I could imagine right then. It was great. They didn't give a fuck that I'd been on a major label or that the thing acting as a paperweight on the coffee table was a Grammy Jordan had won. They were very secure in their skins and in what they wanted to accomplish creatively. I have no idea now what exactly we said, only that it was very stimulating to my thought processes.

After they left and I was brushing my teeth and Jordan was taking his contacts out it struck me to ask. "Hey, didn't you have a boyfriend last time I was here?"

He shrugged and swirled his contacts in their little double-dish with his fingertips. "Yeah."

"Should I not ask?"

"He'll probably be back." Another shrug.

Huh. Maybe Jordan and I had even more in common than I'd realized.

***************************************************

(Hey, we're in 1991 now. This was a hit in 1991. Don't feel bad if you don't remember it, though. Hardly anyone in the USA does. But I do. -d.)

*************************

Kickstarter News!

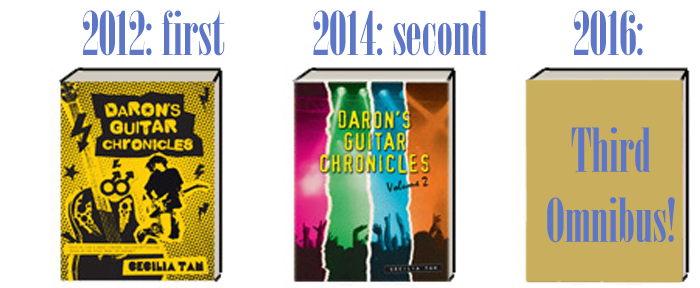

Can you believe it's been two years since the last Kickstarter? It's time to put the next 280,000 words of DGC or so into a big fat paperback like we have with the previous volumes. The campaign kicks off in about 12 hours so if you're reading this after about noon Tuesday, it's live! If you're reading it before that, here's a link to see a preview of all the rewards so you can pick out what you might want: (Link below in comments section.)

Among the cool things I'm offering this time around: DGC temporary tattoos in a few styles, including matching the designs that Daron and Ziggy went and got that night in Los Angeles in chapter 652. Custom guitar picks that can also be had as a necklace. But the big thing is the book itself. :-) It will be close to 400 pages, and if we reach our stretch goals, then like last time it will have some bonus pages and sections, too!

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: Truyen247.Pro