HERE COMES THE SUN

The westerlies brought more snow that morning and Betula was chewing on a third mocha bar while struggling to recall nearly forgotten tidbits of her Meteorology textbook when she noted a hint of a break in the gloom of another dark day. In that class the presumed wind conditions in the Arctic were of little importance to future pilots whose range would remain below the mid-latitudes, but they might just have been in as an extra-point question over the dreadful period of final exams. She vaguely recalled a graph that showed prevailing surface winds blowing from the east in the region's summer. So, what were they waiting for? It finally dawned on her that at 60 degrees North she was still under the Polar Jet Stream, one of those conveyors of weather events such as the storm she was stuck in. If, when, she was to leave Mont d'Iberville, she had to go much further North and escape to a calmer, colder zone. Calmer it better be since the Atlas didn't show much detail on the ice sheet up there or identified elevations likely to offer nunatak refuges until the far reaches of Alaska's North Slope.

A silver lining was forming in the clouds as she told herself that a more Northerly trek would also offer a shorter Great Circle Route. The navigation would be challenging and would take her closer to the Pole but, what-the-heck, what else could go wrong when things were looking up. By midday the snow had dwindled to flurries with sparse snowflakes floating up and down in a light breeze. The sky grew brighter, then cloudless at dark and Betula was treated to her first Aurora Borealis. She was in a spell for hours, at times shivering free of her pitted canopy for a better look.

Going to sleep was not an option. She was too excited, too ready, too obsessed with the routine tasks of her anticipated departure flight in the morning. She was repeating to herself every safety check, every task, she was worrying about every possible mishap, malfunction, disaster. She was a wreck. It was like she was on the eve of her first solo jaunt. Distraction was in order. She had one more disc to watch.

It began with a familiar scene. A graduation ceremony with the usual litany reading of the laureates' names, the families in attendance, the hugs. Just like the Institute except for the weird caps the graduates threw in the air only to quickly retrieve. Precious mementos probably destined to mold in an attic at home. There was a young man, his sister and their parents at a rather tense lunch, some goodbyes and presto the young man gives away his college scholarship money to charity and sets out to disappear, to be free. His adventures as a vagabond were fascinating to Betula who recognized a free spirit like her in some ways, but the peoples he met did not in the least fit the accepted stereotypes of the vile Ancients. They were sometimes cruel, but much more often kind, they worked, they played, they were odd, they made music, they were fun. Maybe it was in the underbelly of the beast that the Ancients showed themselves at their best. Still, that was not enough for the young man who wanted to go North to experience the wilderness, to be free, to survive on his wits. That certainly caught Betula's attention, but the tale's ending was sobering. Unable to return to civilization as cold weather sets in, he tries foraging to survive and eats the wrong part of a plant that makes him unable to digest food and he starves to death. A true story, apparently.

That was not encouraging to someone just about to head into a wilderness even less forgiving than the one the young man dreamed to conquer, but Betula quickly put that concern to rest. Starvation was an unlikely fate. Should a mishap put her down on the flight path she had chosen, she would freeze long before she ran out of protein strips. So be it, she thought and turned in for a very peaceful rest.

LEGENDS IN THEIR TIMES

Not a cloud in the sky, not a breath of wind. The dawn was bright though the sun was still below the horizon. It was a hint of approaching days without nights. After a week of stormy darkness, the change was astonishing. A taste of summer perhaps, though the harvesting of a few icicles for freshwater would have been painful without gloves. It had been hard to free the ice anchors, the gull didn't want to leave Mont d'Iberville it seemed. Hopefully this wasn't an omen, thought Betula while giving a last look at the whiteness on the slopes at her feet, the few leads of milky water parting the crowding of icebergs far out into the Labrador Sea below the dawn's now sparkling at the horizon.

She was tempted to take a spin over the bergs for a quick look, but no, she would go around the mound, retrace her way in. I'm getting old, she thought. Being buried in two avalanches does breed a taste for an abundance of caution and, anyway, it would be frightful enough to see the other side of Mont d'Iberville, the side she could have hit head on had she been drifting a bit further East at arrival time in the storm. With sheer, dark rock faces rising above huge tumbles of ice and snow, it was scary alright and Betula got away with a hard turn West, into the wind just in case there was any, and after a few minutes she altered her course to a northwest heading toward a peak on a crest of ice a few miles away. Steady on the stick. Looking for any hint of her craft drifting, without even a glance at those sastruggis.

She was on a roll. Her first attempt at finding her position was hours away. Meanwhile she would keep the same heading and after recording her observations she would figure a likely path until the next day's noon sight. Over the short nights the autopilot would take over and follow compass bearings that could at times be suspect as she was so near the magnetic pole. So, without charts or ground reference points she would have to rely on dead reckoning, an aptly named discipline here, and use the old Atlas' longitude lines for a guess at her westerly gain. That would give her an approximate series of headings for a Great Circle route. Lots of math, but she didn't have much else to do, did she. It would be a flight of some three thousand miles or more to reach a point at approximately 165 degrees of longitude West and 70 degrees of latitude North. Then, she would go South until she found open water and the Alaskan shoreline well beyond and below the region's rugged North Slope. She would follow the shoreline, southward. It would take a few days and nights to get there. Weather permitting.

She had it easy. Looking over her right wing at the immensity of the ice mantle, she thought of Ellesmere Island, third largest island on the planet, a few hundred miles away. Her Ethnology book told the epic story of thirty-eight Inuits from the island's South shore whose leader had learned from a whaling ship crew that there were other Inuits living across the sea. Hauling twenty-foot-long sledges carrying belongings and kayaks they set out northwards along shores and over glaciers to cross Smith Sound into Greenland and they found there the people they had sought. Their journey had taken six years and they stayed with their hosts as kinsmen for another six years until the old man who had led them there thought he would like to see his own country again before he died. He decided to return home and most of those in his tribe followed him.

Hours after hours passed with Betula in a somnolence deepening into naps now and then. The autopilot kept her craft easily on its bearing, the drone of the engine humming steadily without the rises in pitch that suggest corrections for changing conditions aloft. She set an alarm to make sure that she wouldn't fudge the timing of her noon observations. After that, she found herself wide awake, though she felt dead tired. It had been too short a night. She was thinking of the young man dying alone in the wilderness. He had kept a journal and wrote about his longing for company. He had won his wish for solitude, but at the end of his days he thought that this was not a satisfying fate, that we are not meant to live without the company of others. Betula had doubts too. What was she doing there, heading into the unknown? The challenges of a storm did not allow much concern beyond mere survival, but now, gliding along over a whiteness seemingly without bounds, she was thinking of one of these bounds, the narrow transition between the thousands of square miles of the ice mantle and the thousands of square miles of an ocean chockfull of ice castles. In a fairy tale ending she would follow these shores a few miles and happen to notice a scattering of igloos around the unmistakable shape of a flyglider cozily tucked in under bear skins. Really? What if she missed it, while rounding a rocky cape or neglecting the ocean side of an island? Face it, Betula, if Liriodendron had been camping behind a rise a few hundred feet away from her Mont d'Iberville roost she would not have known it, and neither would he. The whole plan was way beyond reasonable, it was a wild goose chase in the deep of an Arctic night. She would disappear like he did, without a trace, leaving no clues that no one would seek.

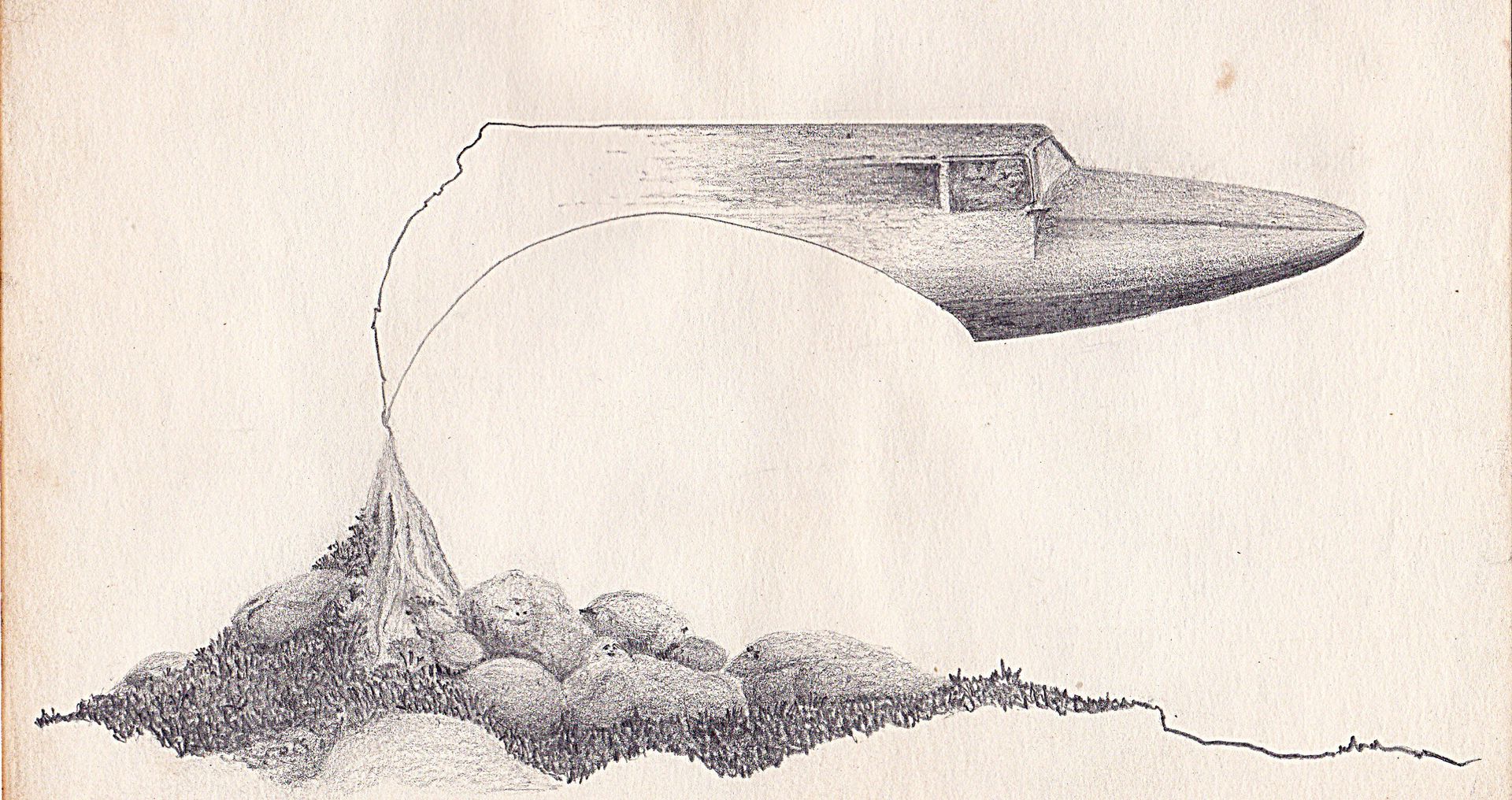

No traces, no clues? It would be centuries perhaps before an expedition found her remains, perhaps some sort of a sack of bones in a bizarre contraption with no clear origin. They might not even speak her language. Why not leave a drawing, like prehistoric cave art, but a symbol of her times. Why not a flying machine risen from a volcano, they would know of the cataclysm for sure. A brilliant idea! Betula fetched one of the many No2 pencils that had cluttered her digs sharpened its point and set to work on a blank page of her neglected log book. It wasn't easy. Last time she had attempted artwork was at home, tutored by her parents and she surprised herself finding she was sticking her tongue out a corner of her mouth while drafting a short, horizontal line. That was fine, she had time.

As the drawing progressed she thought that she and Liriodendron could live in memories. They would, within their families, no doubt. The Personal Disappearance Inquiry would carry on with its work at the Institute. Liriodendron, then Betula, that would look odd. Weren't they a couple? How come they read the same library books, these volumes Betula took with her? Their strange hoarding of protein bars, their huddling together at the library, could they have planned to meet somewhere? Could it be a case of a double suicide? Would Fixit-the-nth break down and reveal her secret plan? No doubt, the tale of the Beauty and the Beast would resurface over drinks at the cantina. Liriodendron would be a slick seal and she would be a mangy bear.

The loss of two flygliders would be impossible to hide from the public. The neo-shamans would harp over the loss of valuable equipment to the caprices of a couple in a sinful union that had not been sanctioned by the Mother, a couple that might be at work obliterating traces and relics of the ancient Mother cult the mongrel Betula had attempted to conceal.

Sadness and despair were again clouding the canopy of the seagull now moving steadily, headed fast and straight for that mythical congress of thousands sardines. Betula thought of a scene she had watched the previous night. Long before he reached the wild country the young man had befriended a very pretty, very young woman, a girl really. She offered sex, but he proposed something else they could do, playing music and singing in a café. They did, they were decent, caring folks like those at home beyond the Institute's confines and the neo-shamans' temples. Perhaps the tale of the Liriodendron-Betula romance would spread to modest neighborhoods, remote villages. Love birds who flew to the ice, they could become legends of their time. Children would scratch graffiti of their initials within hearts on city playgrounds while others, more politically motivated, might use these same initials in LiBerty, or LiBertad. Who knows?

Big deal, but there today looking ahead to thousands of miles on the ice the reality was that Liriodendron was probably dead and her prospects were not much better. All of a sudden she felt guilty. He had to save himself from unjust administrative incarceration, perhaps death, he had a very good reason to escape, but she was a thief, a selfish, harebrained criminal who had appropriated one of a limited fleet of extraordinary machines for a cockamamie of an attempt at rejoining a dead lover. She deserved to die. Where was she? Sooner or later her machine might break down or she would crash land for the last time and freeze in that alien landscape, tumbling about in a windstorm or thrown against an ice cliff or simply laying on frozen ground like the lost souls at Naschwak she had dreamed of. That would serve her right, wouldn't it? What was her life worth anyhow, who could hazard a guess, what was it that she could leave behind other than her sorry hide? What was so special about her sorry hide, pointy fingernails? The sadness was unbearable, she thought again of those dying souls in a death hug, their crying, for justice perhaps. She thought of the old fisherman dying over his dead dog, the unknown soul dying alone in a snowbound shack, even Marcel Desfresnes' twisted apogee. Did she simply dreamed them all or did they reach to her to tell of the wrongness of their fate. And here she was, ready to abandon them again, return their tales to the dark mist that had swallowed them. She thought of Mona's journal, its chronicle of lives. Was that all there could be? Betula thought of her death, of what could survive her in the wreck of a frozen flyglider until one day the North would see peoples return to its ice again. So she turned the page of her logbook and began to write in the smallest hand she could manage with her pencil re-sharpened to a needle point:

"Two millennia had passed since the cataclysm, but the old prejudices had only abated slightly and slowly...."

She felt much better. The autopilot kept the seagull humming along, a low sun scattered tiny rainbows on the canopy's pitted face, it would be dark enough for a show in a while. She would return to the saga of the spunky young woman and the aging lawman. Everything would be fine, it would all turn out for the best in the end, she knew.

Epilogue: BIRD SHIT

It was a Flyglider H, a brand-new two-seater with the power-assisted rotor and the black puma painted on the sides. The pilot stayed aboard keeping the blades rotating slowly while a man in uniform climbed down and took in the sight of a dozen men in the red, white and blue jumpsuits of the Northland Penal Colonies. Shivering at attention, hat in hand, they were lined up by the side of their red and white stripped tent. The soldier had three gold bars on the side of his fur-lined hat.

"Welcome, Sir. Thank you for taking notice of our discovery," said the oldest of the convicts.

"Never mind," came the answer, "show me what you have."

"Follow me, please." The old man walked off a few steps to a gravely slope where you could make out a faint circular outline of some three meters in diameter. "I am quite sure an igloo stood here within the last two years," he said, "you will notice near the center the smudge of black soot, the trace, I believe, of animal oil or grease, burned for heat or light."

"That's bird shit," said the officer.

"Sir..."

"That's bird shit. I know bird shit when I see it and I know bullshit when I hear it. You are only trying to get time off from me. Follow me."

They walked back to the Flyglider where the pilot handed the officer a clipboard and a pen. "It says here that we have investigated on this day a claim of evidence of current human settlement and found the claim to be in error. Sign," he said.

"But, Sir..." The old man appeared to shrink below the hostile glare of the officer who enunciated slowly the gist of the matter. "You are here to prospect for riches, be they minerals or valuable relics. Do not ever bother me again with bullshit or bird shit, else I'll put you on winter duty on the ice."

The old man signed.

Aboard and aloft the officer threw his hat behind his seat, grabbed a mike and punched a few buttons at the dash. "Flyglider H at latitude 52 degrees, heading home."

"You are on," came the response.

"Claim investigated, found to be nonsense."

"Funny, the claimant used to have impeccable scientist credentials."

"Just another blue-eyed moron."

"You don't say... Over and out."

As the clop-clop of the blades ebbed in the distance and an old man stood dejected on a gravel bank, two slight shapes in white furs were squirming away, below a fissure in the ice front.

"I told you they wouldn't be long," said one, stuffing back in her bundle the binoculars she had filched from another prospector crew.

"Oh, Mona, how come you are always right..."

"That's why I got that nickname, my grandmother knew of a Mona, a storyteller of antiquity, a prophet. She foretold all of what got us here."

"Yeah, sure..."

"That's right. And I am telling you now, you and I and the folks, we will be all right around here for another summer or two, but after that, Ellesmere Island here we come, then Greenland, Spitzbergen and Norway. We'll follow the edge of the ice and see what we can make out of Europe. Or else, build kayaks and try Siberia. That may be the way we once traveled. It will be all ours!"

"Sure thing, Mona."

"Well, you can come, or you can stay, and be a slave." Out of her bundle she dug out two pieces of dried seal meat.

"You said we would steal food for the return trip..."

"I know, but those wretches are starving enough as it is."

"Mona, it's a two-day walk."

"I have two more pieces for tomorrow. Protein and fat, it will get us there."

"What's protein?"

"I don't know, but it got my grandmother across the continent."

"She wasn't walking."

"She would now. She is one of our people now. Tough as they come," she said and she handed her companion the other two pieces of meat, "I have to talk to that old man."

"You are crazy, they will kill you!"

"They don't have weapons and I can run faster than they can throw rocks. Go on, I will meet you tonight at the winter camp site. Go on, if I don't make it, tell my grandmother I did what she asked for."

"Mona..."

But she had already turned around and was walking back. Betula had been very clear. "Find an old man or a man with blue eyes. An old man with blue eyes would be best. Ask him if he is going home soon. If he is there for life, run. If he is not, ask him to tell Consuela that her sister Betula is alive and well and says that Santiago's railroad must come to the ice. Then, run."

It had not been easy. Plenty of old prisoners there, but it was hard to tell the color of their rummy eyes at a safe distance. Hence the filching of the binoculars that greatly eased the subsequent spotting of the perfect candidate, just when they were running out of food and that darn machine showed up.

The old man was now dragging his feet on the way to the scratch in the gravel they had for a latrine. He was fiddling with the flap buttons of his jumpsuit when a little bear showed up at his side. The old man let out a yelp and froze. 'Don't try to run, don't do anything threatening,' that's what the instructions said, 'stand your ground, don't rile up hostile wildlife.' But that bear was odd, not a bit hostile and instead of a black muzzle above scary eyeteeth, it had a small, slightly upturned nose under two large, dark, beautiful eyes. And it had a question.

"Don't be afraid, old man, are you going home soon?"

"Three months, the Mother willing," he answered.

"Perfect," said the bear, "when you get home, find Consuela and tell her Betula is alive. And tell her Santiago's railroad must come to the ice." That was all and the beast just vanished, leaving him stunned. By the time he looked around he noted that the bear had metamorphosed into a fast-moving biped already halfway to the ice front. All of a sudden the episode made a lot of sense to the old man. He looked into the hazy skies and said to himself: "I am the happiest man in the North, today," and to the fading silhouette of the Flyglider, he whispered slowly: "Bird shit eh, you ignorant bastard, we will make you eat it someday."

The End

Note. Artwork by the author.

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: Truyen247.Pro