CAPE FAREWELL

All of a sudden it wasn't as much fun anymore. Heading to warmer waters meant we would be facing southerly winds when every dip of the bow, every gust, every flap of a sail would offer a splashing sample of whatever would eventually pass for summer beyond the Arctic Circle. The jet stream moved lows after lows that had passed over the New England regions without much notice or damage beyond the overturning of a few umbrellas, but by the time they reached us they were just as nasty as the one we had encountered on our way North and they were followed by the same slams of cold bred above the remaining polar bears of Canada's northern islands.

Worse, we had turned our back to the stunning displays that eased our nightly watches now and then, the sky wide curtains, the curving pillars, the undulating clouds of green phosphorescence, the ever changing displays of the Aurora Borealis. Sure, we could look over our shoulder or sit on the cockpit sides, but it was not the same; we were not heading there and we knew they would soon disappear below the horizon. We didn't talk much beyond our ordinary communications and April spent most of her free time below, poring over books and maps. Close to the Greenland coast we did see a flock of dovekies, small stubby birds floating perfectly at ease between wave crests, a fulmar, a few gannets, even a Tern just in from Antarctica perhaps, but the seabird colonies were onshore where they were settling into the feeding of their young.

Fifteen centuries ago, the southern tip of Greenland was an important landmark for the Norsemen traveling between Scandinavia, Iceland and their settlements on the west coast of Greenland. Their ocean going ships, the knorrs, were about the size of Onward, but higher sided and narrower. They were only decked at bow and stern, carried ten to fifteen peoples, supplies, lumber and livestock. Navigating by sun and stars and informed by the presence, or absence, of seabirds and whales, the Norsemen left the south coast of Iceland behind and headed far enough to pass west of Cape Farewell, but not so far as to run into what they called the Land of Stones better known today as Baffin Island. Heading east of Cape Farewell was, still is, not recommended. There, the shore rises hundreds of feet from the sea to a basin where the ice sheet has piled up to reach depths of five thousand feet. Today there are only a few automated weather stations and a couple of settlements on the hundreds of miles of that shore. In Viking times, there was nothing but ice and rock.

April had mentioned that our intended itinerary was to include the Straits of Denmark, which actually are nowhere near Denmark but refer to the narrows between Greenland and Iceland where the Atlantic Ocean becomes the Greenland Sea. I did not think much of the idea; it would take us back to the Arctic Circle and double the length of our trip to the British Isles, but when she appeared at the companionway and announced that we were on our way to the top of the highest waterfall in the world, I thought that this time the woman had lost her marbles.

Google is dangerous. It has much factual information about everything but few concerns about sailing the Denmark Straits. While studying the ocean currents and choosing our route over the relatively warm stub of the Gulf Stream along Iceland's north coast, April lost herself online and ran into a take about a waterfall unknown until recently for a very good reason. Unseen and unheard, it starts its jump some two thousand feet under the surface of the straits and drops twelve-thousand feet over the side of the European continental mass and into the depths of the Atlantic. April said we could not ignore that wonder; Google cited the second highest phenomenon of that kind as half its height and near Brazil. We just had to go through the Straits and she wished we had something to drop overboard to honor that marvel. I didn't volunteer.

So we would sail the Straits, but Google can be really, really dangerous. April had gone another thousand miles further, to Svalbard, also known as Spitzbergen, a large archipelago pretty much unknown to most until it became a popular summer destination featuring striking landscapes and a petrified tropical forest, she said.

That was a step too far. Not only was Svalbard quite close to the Polar North, but featuring a tropical forest? I urged April to dip a hand overboard and tell me how tropical the water felt, but again I was the uninformed fool in the conversation. Continental drift brought the archipelago to its present location after the breakup of Gondwana in the Devonian Age, she said. The forest apparently had not survived the trip and turned to stone over the following million of years. This kind of information had once crossed my learning years without leaving much of a trace and I wondered how a Tasmanian school's truant was so knowledgeable about such matters.

"These books my father bought," she said, "they were textbooks, way over my head. He knew what he was doing. On long passages you can get so bored, you will read anything with pictures and charts, even when you need a dictionary. He was quite the old-fashioned man, we actually had an Encyclopedia Britannica." I felt like being old fashioned myself, I added up the miles, going there and coming back. It was like planning vacations with the kids; Yellowstone, no way, Disneyworld, maybe next year. And here I was, sailing along the Arctic Circle again, not that far from the North Pole and feeling like the Grinch.

So we went over the waterfall. April threw overboard a pair of hoop earrings, gold, in color anyhow. "They belong to that girlfriend of my dad," she said, "the one who read my diary, she can come and dive for them anytime." I kept my mouth shut, I was quite pleased with our compromise. Summer already felt like fall; past Iceland we would take a southeast turn, rejoin the way of the Norse sailors returning to their settlements in Scotland and its northern islands.

SLICED POTATOES FROM A CAN

There were more damn boats. Fishing boats, freighters, pleasure boats, power or sail, even a couple of billionaires' megayachts probably taking their cargo of fat moguls and skinny models to the Arctic Circle for a thrill. And trash; occasional rafts of crumpled sheet of plastic entangled with lines and foam floats with gulls circling above. The weather was summer like, with mellow southwesterly winds. April decided to pass the Shetlands and go south to find a discreet harbor if there was such a thing on the coast of Scotland. We were running low on oats and maybe I could go shopping for her. We didn't have much to talk about; Onward was traveling under a somber pall. April kept grumbling about the nosy crews of vacationers who approached us just to wave, it seemed. She had not returned her now stored British flag to the stern.

I should have been happy, my task was nearly done. I had to get home to make sure I would have enough firewood for the winter. All I could probably buy would be 'seasoned' stuff, meaning just cut down and dripping wet; maybe I could cut some dead-standing spruce. I was dreading the trip to London, the transatlantic flight, the bus trip back home. When April asked me to retrieve her spare inflatable from the lazarette and get it ready, I realized that I did not want to pump up that rubber thing, I did not want to get into it. I did not want to leave Onward, but a job is a job and a deal is a deal.

April had found our port of call, Colbeth Island, off northeastern Scotland. There was a ferry to a big town on the mainland, an airport there. I was done. "Why can't you drop me off closer to London," I asked, "you are going south anyway, aren't you?"

"Why would I go South? I might go across the North Sea to the Baltic, do the Norway coast, hell, why not try to spend the winter in Svalbard..."

"That's crazy! You will freeze to death up there."

"I am crazy Sam, haven't you noticed?" She was right, I felt very sad. I pumped up the darn inflatable, tied it down to its chocks with new straps. "Don't be so morose," she said, "if we get into Colbeth Harbor early enough we can have a goodbye party." Sure, I thought, we'll cook the oats with the peaches but I felt a little better. Ashore I would soon find a burger and fries somewhere.

Well protected by a row of massive boulders the harbor was a surprise. On approach we noted a superstructure that dominated the island but did not look like a ship. Closer we could see that it was a massive platform, one of the rigs that drill the seafloor for oil, probably parked there until its next assignment or decommissioning. The harbor had a few fishing boats and some industry service crafts, plenty of space left over, no pleasure boats. It was perfect, there would be no one to row over and chat, or invite us for drinks. We dropped anchor as far as we could from the fleet, bagged the genoa, even tied down the main under its sail cover. Shipshape and Bristol fashion, my first and last time aboard Onward.

It was April's turn at the stove and she went down with a "supper at eight!" and a chuckle. I peeled off my gear and sat in my jeans and t-shirt looking at the sun going down over the village. It was strange, the boat was still, I felt warm. We weren't sailing or drifting for the first time since we had left Maine months ago. There were distant, unfamiliar sounds, a barely audible conversation, dogs barking, a car door slamming, the engine firing, accelerating, vanishing into silence. Quiet place, reflections on the water between silhouettes of boats under the few street lights ashore, homes lit against the shape of a hill below a darkening sky. Down in the galley there was a knocking of pans, the crackling of frying, an unfamiliar smell, silence.

The first ring of the church bell startled me but I did not even breathe over the next seven, a sweet souvenir of days long gone over another sea. I gathered my gear and went down the companionway.

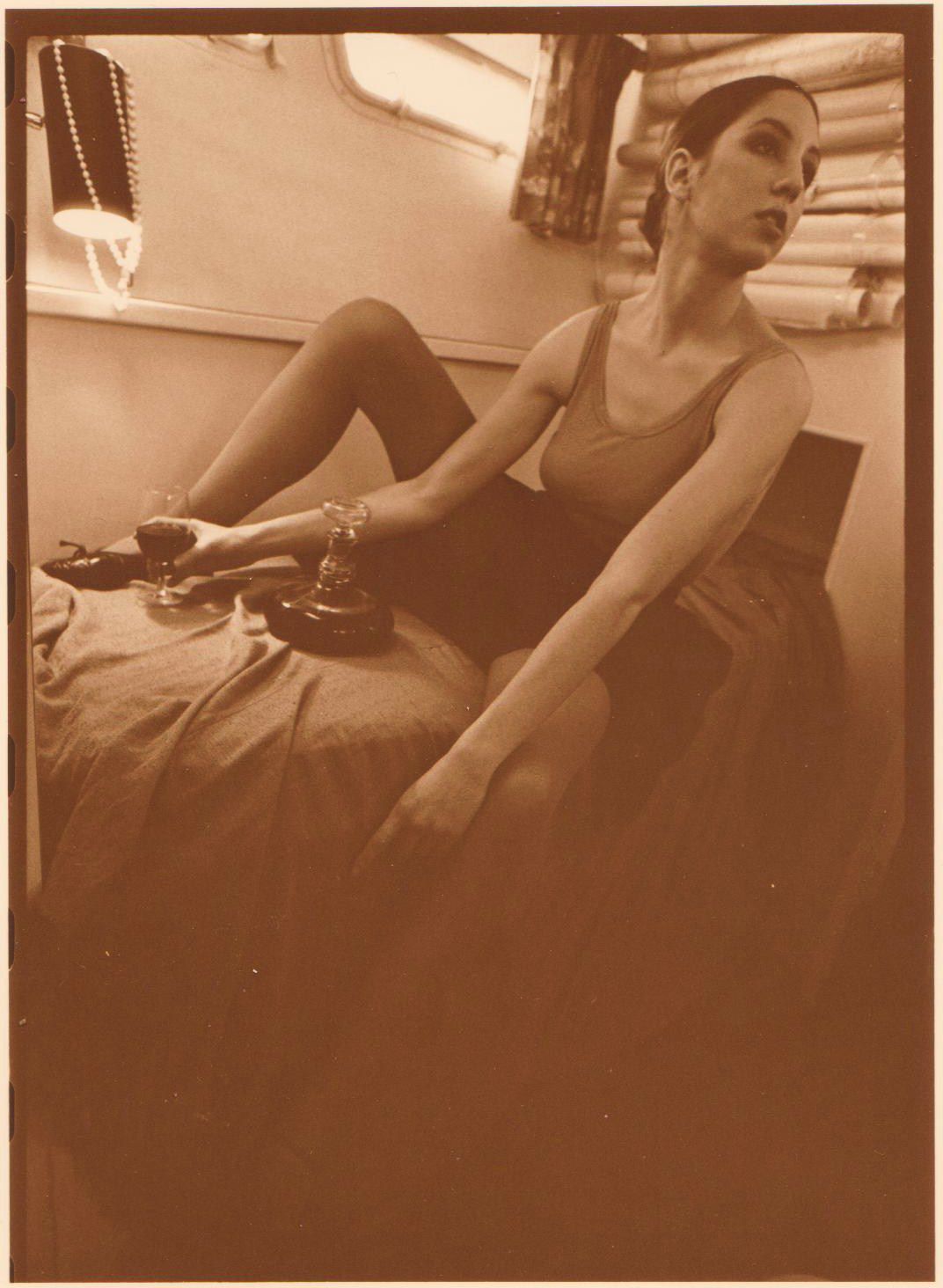

April was sitting on a bunk in skirt over tights, skimpy top, bare arms, hair loosely tied. She had a cut-crystal flask and a glass next to her; another glass was on the table with two plates of something steaming. I was speechless.

"Sliced potatoes from a can," she said, "I forgot I had them.

"You are beautiful," I said.

"Don't get any ideas."

"I don't see any shotgun..."

"I thought I had supper with a gentleman."

"You are," I said.

We raised our glasses to health and prosperity, more for mine than hers, I thought. Fried in olive oil, the potatoes were a surprise and the peaches delicious, warmed in their sugary juice with a touch of the flask content. "Jack Daniel's," she said, "my father's favorite. He drank lots of it when he was singing in a country band and part-timing in the darkroom. That's when he met that woman and knocked her up. By the time little me was born, he had quit drinking and he was working full time in the dark."

After some more chitchat we were both dead tired and the little we drank wasn't helping. We planned my resupply trip. She had a piece of paper with a bank's name and a number. "I am short of cash, you might have to go to Edingburgh," she said, "you can't go to an ATM in a mom-and-pop store and take out lots of money, the cops will be on your case. Try four withdrawals, at different banks, two-hundred and fifty pounds each." I wasn't enthusiastic about that prospect, but I wanted to help. I picked up the dishes and she rinsed the carafe, then we headed to our bunks. I had to thank her properly. "Great dinner," I said, "I was not fooling earlier, you are a beautiful woman." She wasn't long with an answer, "fat lots of good it does for me." Not exactly a coquette April, my kind of babe.

NEXT, HOMEBOUND.

Bạn đang đọc truyện trên: Truyen247.Pro